Steve Biko: Life, Death and Legacy Exhibition

By jackgreeney

If you go to the Students’ Union on Wednesday the 20th or 27th of March and you might discover that the building you have entered has a different name entirely to the one you are used to. Since 1977, the Students’ Union has actually been called ‘The Steve Biko Building’. No, really -–look it up, it’s all there on Google. The problem is that, somehow, nobody seems to know this, and perhaps somewhat relatedly, a pinboard at this exhibition titled “Do you know who Steve Biko was?” was mostly stamped with ‘No’.

Written and curated by Elias Mendel and designed by Marlo Plowden, ‘Steve Biko: Life, Death and Legacy’ hopes to change that. This exhibition proudly states that Steve Biko is “widely regarded as the founder of the black consciousness movement in South Africa.”

Information presented is concise and educational, contextualising Steve Biko within the legally enforced racial inequalities of South Africa. There is also insight into his Xhosa heritage, with his real forename ‘Bantu’, meaning “one for the people”; an apt name for the activist.

“Apartheid”, now so firmly written into the English lexicon, is Afrikaans for ‘separateness’, the segregation policy enforced by the South African Government from 1948. The facts are jolting – as a result, South Africa continues to have the worst economic disparity of any country to this day. Some would say Apartheid is not yet over at all.

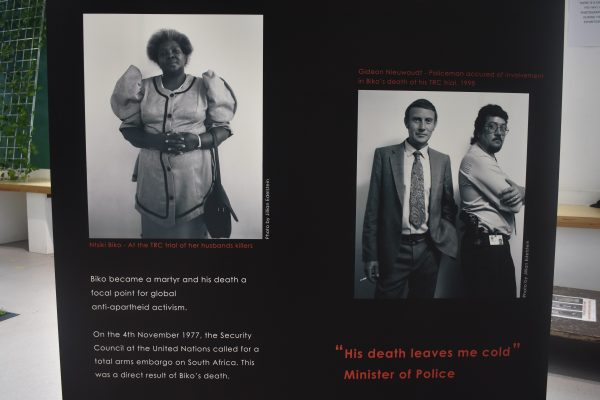

The photography of separation is striking too. Split scenes of ‘white’ and ‘non-white’ areas come with shocking reminders of how recently this all happened – Apartheid was still in place until the early 1990s. There is certainly a coherency to the collection, of oppression, consciousness, and radicalisation; from Biko’s formative early years to his beating and manacling under police custody in 1977, a death labelled “an accident.”

Portraits of Biko’s surviving family, placed in stark contrast to shots of the policemen accused of his murder, are particularly effective in stirring up the emotions of injustice. Footage from Biko’s speeches and mass protests at his funeral at the end of the exhibition is a nice touch too. Here there is also featured artwork of Biko from local artists, although this could have been displayed more prominently.

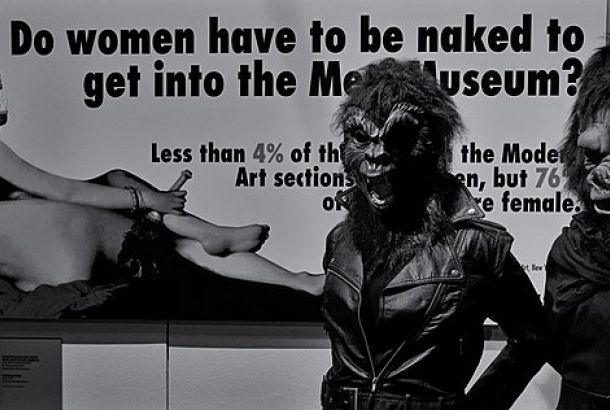

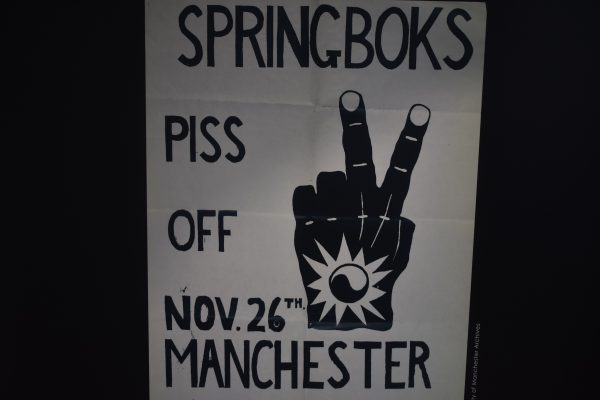

The role of students in combating Apartheid is also shown, displaying posters from the South African Students Organisation (SASO). Some are simplistic and effective – a black, raised fist imposed on a white background. Others are convoluted and emotional – bizarre mangled bodies squashed into a corner on a black page.

Returning locally, University of Manchester pamphlets produced during Biko’s imprisonment in 1969 are also displayed. The University of Manchester’s “history of divestment” from governments enacting atrocious segregation policies against groups of their own population is well documented throughout the exhibit, which may lead to some drawing a parallel between 20th century South Africa and 21st century Israel.

This exhibition uses a variety of jarring photography and media from history to present a far too often overlooked figure in world history.