The mysteries of the infrared universe: What the James Webb Space Telescope has revealed so far

With a final cost of almost $10 billion, the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) on Christmas Day 2021 was over 20 years in the making. Since reaching its final destination of Lagrange point 2 (L2) on January 24 2022, Hubble’s successor has ushered in “the dawn of a new era in astronomy,” with its ultrasensitive detectors providing an insight into the hidden infrared universe. So what has the JWST revealed so far, and what does this mean for our understanding of the universe we live in?

The beginning of the universe

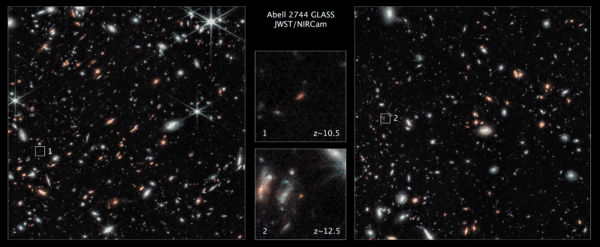

Just a few days after embarking on its mission, the JWST captured images of two of the most distant and earliest galaxies ever discovered. The two galaxies, named GLASS-z10 and GLASS-z12, appeared as unusually bright objects in the GLASS-JWST images.

Using spectroscopy, a process in which scientists measure the ‘red shift‘, or stretching of light towards the infrared end of the spectrum as an object moves away from us, researchers can estimate that GLASS-z10 and GLASS-z12 date back to 450 and 350 million after the Big Bang, respectively. This makes GLASS-z12 the oldest galaxy ever discovered at around 13.5 billion years old.

At this point, the universe was in its infancy at only 2% of its current age and the galaxies themselves must have begun forming even earlier. The previous record holder, GN-z11, existed 400 million years after the Big Bang and was discovered by James Webb’s older sibling, Hubble.

“It’s like an archaeological dig, and suddenly you find a lost city or something you didn’t know about.” – Pascal Oesch, National Institute of Astrophysics, Rome

The end of the cosmic dark ages

As well as revealing some of the oldest known galaxies, the GLASS images are challenging our understanding of the early universe. The cosmic dark ages, when the universe was engulfed in clouds of neutral hydrogen before the birth of the very first stars, were thought to have lasted for several hundred million years. The discovery of these ancient galaxies questions this theory, suggesting that galaxy formation began as early as 100 million years after the Big Bang.

In addition, these galaxies are far bigger and brighter than expected in the primal universe, with masses of up to 100 billion times that of the sun. Our current models of galactic evolution are unable to explain the quick formation of these galaxies, as the universe did not contain enough gas at the time to form as many galaxies as have been found by the JWST.

Although further investigation is required to fully understand the formation and composition of these ancient clusters, the JWST may result in a shift in our current understanding of the young universe and its contents.

The birth of stars

The JWST has not only captured the oldest parts of our universe, but also the creation of new ones. Researchers can now see the formation of a protostar within the dark cloud L15278, hidden within the neck of an hourglass of material feeding its growth. As this material is ejected away from the forming star, it collides with surrounding matter to form cavities which are illuminated by the leaking light to form blue and orange clouds above and below.

As the protostar gathers mass from the surrounding gas and dust, the material spirals around the centre to form an accretion disk, a dense ring of material which feeds the growing star. Seen in the image above as a dark belt across the bright centre, the accretion disc of this protostar is about the size of our solar system and gives us a peek into the birth of our own Sun and solar system.

Other worlds

Researchers are aware of more than 5,000 exoplanets: worlds that orbit stars outside of the Solar System. Despite this, very little is known about most of them. The JWST is giving us access to these other worlds as never seen before.

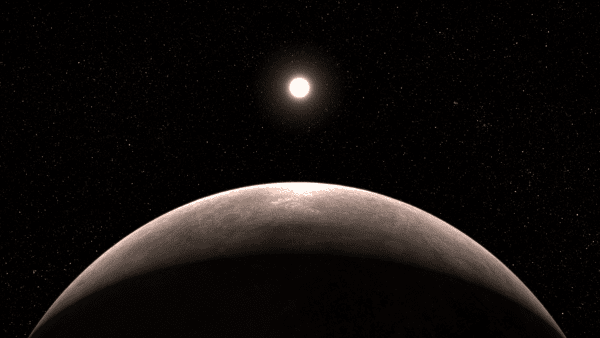

The first exoplanet discovered by the JWST was LHS 475 b, a rocky planet which has a diameter equaling 99% that of the Earth’s and is only a few hundred degrees warmer than our home. This earth-like exoplanet orbits its star in just two days, which is far quicker than any planet in the Solar System, and the red dwarf it orbits has a temperature of less than half that of the Sun.

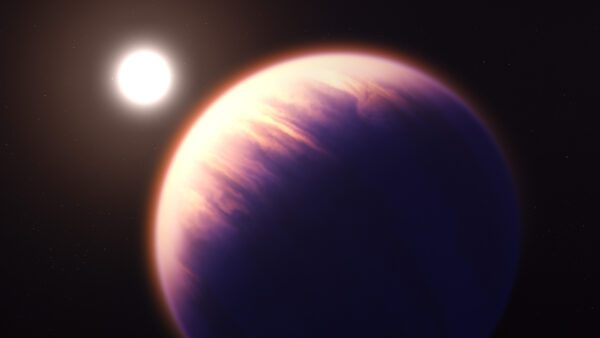

Images of another distant world, WASP-39 b, have revealed the detailed molecular and chemical composition of an exoplanet for the very first time. Described as a “hot Saturn”, this planet lies eight times closer to its host star than Mercury is to our Sun, around 700 light years away from the Earth, with an atmosphere composed of sulphur dioxide, water, carbon monoxide, sodium and potassium. With this data, researchers are able to study the effects of solar radiation on exoplanets, and gain insights into the formation of planets across the universe, including our own.

Closer to home

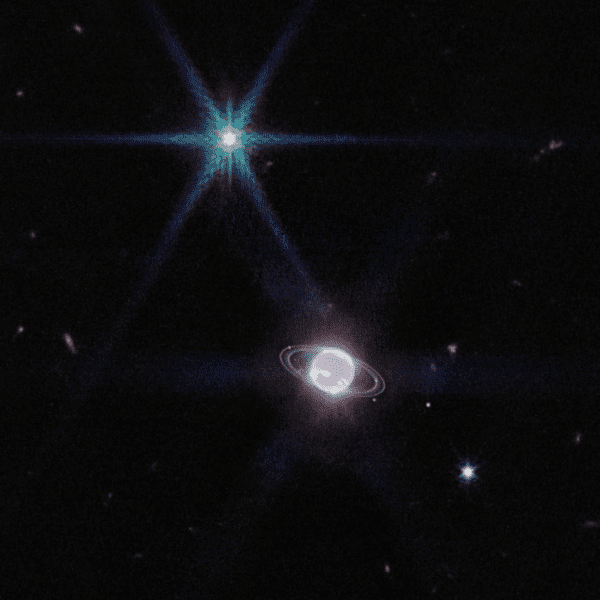

The JWST is also supplying a clearer look at the Solar System we call home, on the outer spiral of the Milky Way. It has so far revealed the clearest image of Neptune’s rings in over 30 years since they were detected by NASA’s Voyager 2 in 1989.

Sitting in the dark edge of the Solar System, the sun is so far and faint that noon on Neptune resembles a dim twilight here on Earth. The image captured by the JWST reveals details of Neptune’s stormy atmosphere, as well as seven of its 14 known moons. The ice giant’s largest and most unusual moon, Triton, is seen as a bright point in the upper left-hand corner.

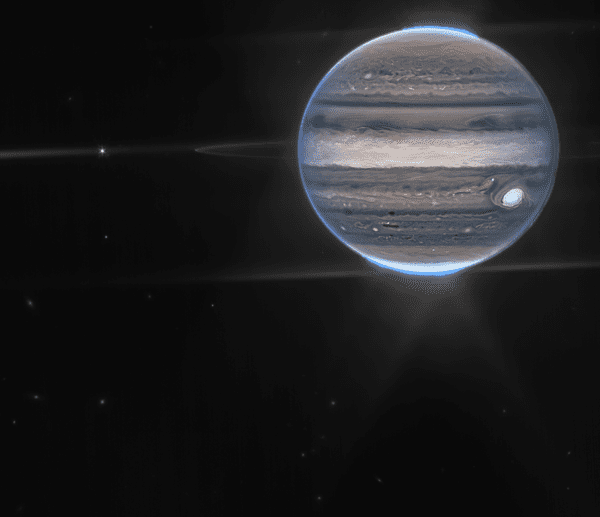

Images delivered by the JWST have also featured Jupiter, with glowing auroras lying above the northern and southern poles, and its faint rings and two moons orbiting the planet.

Nine more years of discoveries

Having completed just over one year of its ten-year objective, the JWST has only just begun its mission to reveal the mysteries of the infrared universe. Not only will JWST continue to show us new perspectives of the universe we know, but also discover things scientists are yet to even imagine.

“There are tens of thousands of scientists — and frankly, some of them just got born or are not even born — who are benefiting from this amazing telescope because it will be with us for decades.” – Thomas Zurbuchen, Associate Administrator for Science, NASA.