Fallowfield’s 18.35%: Why are students not voting?

By rubycooper

Both the 2022 and 2023 local elections saw Fallowfield having the lowest voter turnout of all of Manchester’s constituencies. Just 18.35% of the electorate voted in May 2023, a slight increase from the 15.22% seen in 2022.

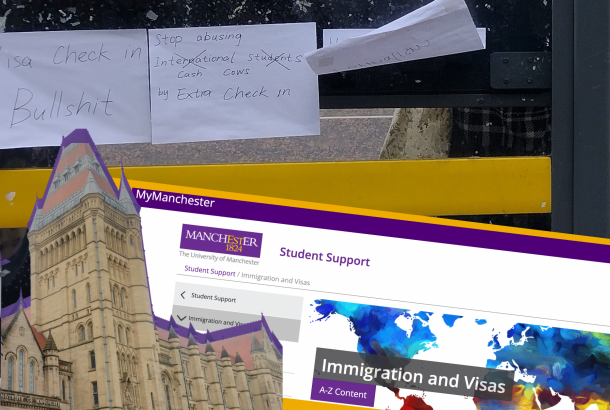

Despite what these electoral statistics may suggest, students within Manchester have never had a passive approach to politics. At the University of Manchester, students are behind the organisation of continual pro-Palestinian protests, Rent Strike movements, and the Reclaim the Night campaign, to name only a few in recent months.

So, if politics is an essential aspect of many student-led initiatives, what has inspired the disengagement when it comes to the electoral system? Rachel, a second year English Literature student, believes the student lifestyle could be at fault:

“Though political conversations are often talking points, students are incredibly preoccupied with living alone for the first time, feeding yourself and keeping on top of your degree (essentially learning how to survive as a human) are understandably higher priorities.”

Meanwhile, Luke, a second year Economics student, expressed his frustration with the registration process, suggesting that its lack of clarity and ease was one of the many barriers students face when deciding whether to vote:

“I wouldn’t know how to vote in Manchester, and I wouldn’t want to travel home from Manchester with the sole purpose of voting either. I just don’t feel the urgency to try and figure out how to do a postal vote for a local election that I might with a general election.”

This dismay toward the electoral system is not an individual sentiment. According to the Electoral Commission in 2022, only 60% of 18–19-year-olds, and 67% of 20-24-year-olds, were registered to vote. With the population of 18-24-year-olds in England and Wales in May 2022 being 5.36 million, making up approximately 11% of the population, this data exposes that millions of eligible voters in the local elections went unrecognised simply because they were not registered.

These figures show the reality that the student population would have significantly more political sway if their registration numbers were maximised.

However, it appears that despite students’ concerns with the exertion required in the voting process, the regulations are only getting more elaborate.

On April 28 2022, parliament passed the Elections Act, which requires voter identification to be brought to all in-person polls in order to be eligible to vote. Accepted forms of ID include a driver’s licence or a passport, but critically not a student ID or a national railcard. It is also interesting that an Older Person’s Bus Pass or a 60+ Oyster Card funded by the UK government is valid at the polls, unlike the youth travel cards that students might possess. If barriers are being placed against student enfranchisement, what is the justification for these changes?

The law was introduced to combat instances of voter fraud but is seen to be a very contentious decision. The Electoral Commission has found no evidence of large-scale voter fraud within the last five years, with only 9 cases between 2018-2022 resulting in convictions; generally, it finds that most instances of electoral fraud are resolved by the police taking no further action.

The Mancunion spoke to the chair of UoM’s Young Conservative Society, Leo Parker, about how he believed this law might affect the ballot box:

“If you want to go out and vote, it’s not much extra trouble. Most people will already have ID, and if you don’t, you can get it for free.”

He believed the extra effort the decision may create is justified, as “even if there’s only one case of voter fraud, it undermines the whole system, and it is an offence to every other person who has cast a legitimate vote.”

In contrast, when speaking to the treasurer of Manchester Labour Students, Fraser McGuire had this to say:

“You don’t get sent free ID when you turn 18. There are ways you can apply for it, but it’s just another barrier.” The search for acceptable forms of ID is something that he argued would only negatively impact the electoral process, as “even if it only affects a small number of people, it still disenfranchises people from voting, especially young people.”

Academic research presented to the House of Commons predicted that the voter ID changes may result in 1.1 million fewer votes in the next general election. Many worry that the cases of voter fraud in the UK are not proportionate enough to constitute the disenfranchisement the decision in the electoral process may facilitate. Despite this, the decision still stands; if you plan to vote next year, you must bring an appropriate form of ID.

But the introduction of ID to vote in-person is not the only issue both spokespersons felt the need to highlight. The misconception that you can only register in one place for local elections is rife among young people.

Many students who are originally from outside Manchester forget that you can register not only at your home address but also at your student address. If you are worried that your constituency either at home or at university will not secure a seat for your party of choice, you can influence the outcome of both. Of course, when it comes to the general election, it’s only one vote per person.

The electoral process is undoubtedly influential in informing whether a young person decides to vote, but is the lack of circulation about the importance of voting within student circles also partly to blame?

Manchester, as a city, is consistently a hub of political activity; October 2023 saw Manchester as the host for the annual Conservative Party Conference. Several major changes were announced: the cancellation of the HS2 project, the replacement of A and T-Levels with the Advanced British Standard, and the intention to phase out the sale of cigarettes and tobacco for the next generation.

The Conference brought politics back to the heart of the city, but not necessarily to the heart of the institutions within the University.

Despite the Students’ Union’s (SU) reluctance to be particularly political, it is not devoid of activity when it comes to promoting democratic awareness among young people. In fact, the student voice is vital in influencing the occasions where the SU takes a political stance; for example, the SU held a vote on February 3 2022, that saw “a formal recognition of the state of Palestine” and a call for the University to “divest any funding given to companies complicit to Israeli occupation and human rights abuses.”

To find out more about how politics operates within UoM’s Students’ Union, we spoke to the Union Affairs Officer, Hannah Mortimer, whose role is to communicate between student interests and the SU.

When asked how the Students’ Union helps to shape student political engagement, she said, “I know we’re hosting workshops, but I think the barrier to stuff like workshops is you’re going to get people already interested in politics that come in.”

“It’s thinking about how we can really access groups of students that don’t get involved with politics for whatever reason, and maybe it’s because they don’t think they have a voice. Maybe it’s because they’re an international student, and they don’t think they can vote (which they can)… really educating students on myth-busting is something that we could definitely focus on running up to general elections”.

Ultimately, she said the best way for your political voice to be fostered around campus, other than engaging with political societies, was to post on the Students’ Union’s Suggestion Page: “If you have something that you want to see, just post it there. If it is a big thing, it will be included in the next Union Assembly.”

The Student Union has seen a flurry of political activity this semester despite the election being months away.

On October 26, the SU hosted an evening with Coventry South MP Zarah Sultana, an event which Hannah said was important to “keep that kind of political voice ongoing throughout the student body.”

Furthermore, the Union worked alongside the National Union of Students (NUS) on ‘Manifesto For Our Future Workshop’, conducting surveys and conversations about what students wish to prioritise in the next general election.

“The purpose of us doing that kind of work, gathering student opinions, student voice, and then working with students to get a manifesto is so that students feel like they’ve tangibly contributed to something. Even if they can’t vote, they’ve put their voice in something that will be voted on; all will be taken into account.”

Though the University does have some internal engagement with the student vote, there are external initiatives whose sole purpose is to promote student voting levels, demonstrating an awareness that there is an active political disengagement among young people that needs to be addressed. One such organisation is Shout Out UK (SOUK).

The social enterprise has previously been praised for organising the 2015 Youth Leaders’ Debate, a live-streamed event with a youth representative from all seven major UK political parties debating various issues. SOUK’s mission statement is as follows:

“Founded in 2015 to protect and amplify democracy, Shout Out UK (SOUK) is a social enterprise on a mission to ensure that political and media literacy education is available to everyone, regardless of their socio-economic background, ethnicity, or gender and safeguards democracy and our rights for generations to come.”

From workshops to articles and podcasts, SOUK accentuates the need to engage young people in political discussions through any means necessary, with the fear that a disinterested attitude may follow this generation into their adult lives.

It is not just the youth that demonstrates an inherent dissatisfaction with both ends of the political spectrum in recent times. Events from the protests outside of the Conservative Party Conference to Keir Starmer being glitter-bombed while giving a speech are suggestive of a proportion of the public that feel their needs are not being met or that their voices are not being heard.

With this climate as the backdrop to the next set of elections, it will be interesting to see whether the student vote will continue on the trend of disengagement or if it will become more active in the quest for reform.

Fraser McGuire from Manchester Labour Students summarised his thoughts on why students should turn up to the polling stations, saying that “politics and the democratic process is happening regardless of whether you are involved or not… if you’re not actively trying to make a difference, someone else is going to be listened to.” He argues that in recent times, “it’s not enough to ask a government to do what we want. We have to make them do it.”

It is undeniable that this coming year is set to be pivotal for all political parties in the build-up to deciding who will next reside in 10 Downing Street.