Boy Swallows Universe: Does reality make the best fiction?

Novels offer insights that often feel more than skin deep. Windows can be opened into fantastical worlds whilst narratives closer to home can re-contextualise real-world issues for the reader, altering their perspective. Regardless of the importance of a novel’s subject, the reader assumes that, unless told explicitly otherwise, the work they are reading is fictitious. A fabrication. So, what happens when, halfway through a book, the rug woven from that assumption is pulled out from under you?

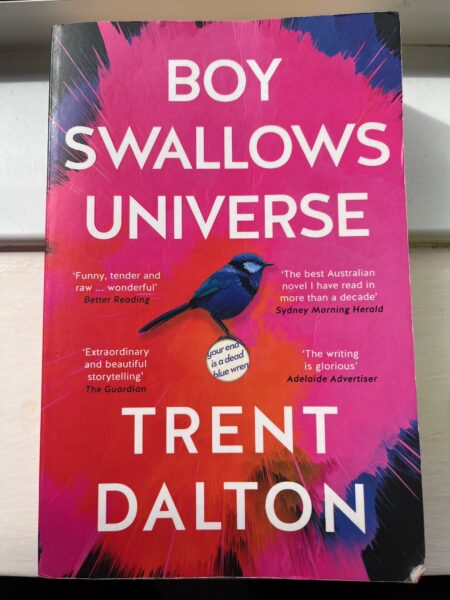

First published in 2018 (and recently adapted by Netflix), Boy Swallows Universe is the debut of Australian journalist Trent Dalton. I was drawn in by its dynamic prose, unique authorial voice, and ability to balance brutality and tenderness. If you’ve considered reading the novel, I would truly recommend it. I will go into some details here, so before continuing, dash to Blackwells, turn those pages, and update your Goodreads. All done? Brilliant, let us crack on.

Boy Swallows Universe follows the adolescence of Eli Bell, who, on the surface, belongs to a classic suburban family. But Eli has seen more than enough to know the truth. His parents are heroin dealers, deep in the criminal underworld. Halfway through reading, something scratched at the back of my mind like grit in the windscreen wipers. The details seemed too specific; the conversations too off-beat to be fabricated; the scenarios so outlandish that the author would surely pause and think, “I might have to reel it in there.”

I undertook some Googling. Now, I’m certain many readers were fully aware going into the novel that Trent Dalton had drawn heavily from his own childhood, but I certainly was not. I had just read 300 pages of autobiographical fiction (a paradoxical genre if there ever was one), and it genuinely shocked me.

I flew through the rest of the novel (I challenge anyone not to devour the final 80-page chapter in one sitting) and personally found this reading experience to eclipse the first half. This raised several questions. Do I enjoy books more when I know the stories behind them? Did the characters become more genuine when I knew they were based on actual people? And how would my reading experience have differed if I’d never learned of Dalton’s personal touches? Would Eli Bell’s story stick with me as intensely as it has?

Desiring art’s context is certainly not a new phenomenon, nor is it individual to me. Just consider Genius, a whole website dedicated to unpicking lyrics. In fact, the notion that stories must originate in the artist’s life is far more common in music. When your favourite artist releases a song about heartbreak, you just have to figure out who they’re losing sleep over. This is only enhanced if it could be about someone else in the band: the mythologising of Fleetwood Mac’s behind-the-scenes turmoil or the constant sprats between the Gallagher’s spring to mind.

Worryingly, this has reached its zenith with the use of rap lyrics as evidence in trials, having led to the continued imprisonment of Young Thug, amongst a variety of charges. Whilst it is ridiculous and dangerous to use artistic expression in a criminal court of law, does this imply an inherent assumption on behalf of many of us that all art is autobiographical, at least to an extent? After all, ideas don’t come out of thin air. The more personal a story, often the more universal its message. But how far can this really stretch?

Most characters in fiction will have some real-world grounding. Perhaps the patter of an aunt inspired how a supporting character’s dialogue is constructed, or a piece of advice the author received in their own life could be transposed into the narrative just when the protagonist needs it. However, Dalton’s family friends were far less anonymous than those whom most other writers draw from.

Slim Halliday is introduced as Eli’s babysitter in the novel when, in reality, he was Dalton. Slim was also a convicted killer, famous for his numerous attempts at escaping prison. Slim is such an outlandish, contradictorily likeable character that he feels as if he must have been constructed; he so perfectly encapsulates the novel’s themes.

Throughout, Slim always protests his innocence, and I took the character at his word. However, upon my discovery that Slim was a genuine figure, I had to reckon with the fact that a taxi driver lay dead, potentially at the hands of the man Dalton had me face-to-face with. The weight of this instantly grew. Does this make me more forgiving of the fictional than the people around me? Perhaps I feel I know them better, certainly if they’re a point-of-view character. We can get inside their heads far easier than the people we pass every day. Plus, the stakes are undeniably lower if we know the events depicted didn’t actually occur.

Through my own warming to Slim as a reader, both Eli and I had to reckon with the moral queries Dalton faced in his own childhood. What makes a good man? Do our worst acts define us? Eli is surrounded by wolves in sheep’s clothing and good hearts in cracked shells. Slim opens the novel with compassion, teaching Eli to drive. He is also a convicted killer. I believe that characters like Slim serve to encapsulate the novel’s themes not because they are constructed to do so, but because they are at the root of the questions that formed Dalton’s reality. Which also raises the question: does the story or feeling come first? Has Dalton used his own life to reinforce the novel’s themes, or is writing a novel of this nature only possible through personal experience? I would truly love to hear his answer.

I don’t believe that all art needs to be as personal as Boy Swallows Universe, but when it is, the discerning reader recognises it (perhaps only subconsciously), and the work becomes all the richer for it. It is the very inseparability of fact and fiction that gives the novel its magic. Dalton has used his artistry to make sense of a life beyond the ordinary and to give hope to others suffering from poverty, crime, and dysfunctional families. Through writing this piece, I have realised that Eli’s happy ending is so powerful because it could never have been written if Dalton had not found his own. It’s a moving thought, and one I hold onto as I return this wonderful story to the shelf.