Review: John Stezaker’s Still Life

Conceptual artist John Stezaker has arrived at the Whitworth, showcasing work that challenges the assumed conventions of photography and aesthetic sensibility.

The exhibition is a combination of 19 pieces gifted by Karsten Schubert to the Whitworth, as well as the presentation of three more collages by the artist himself.

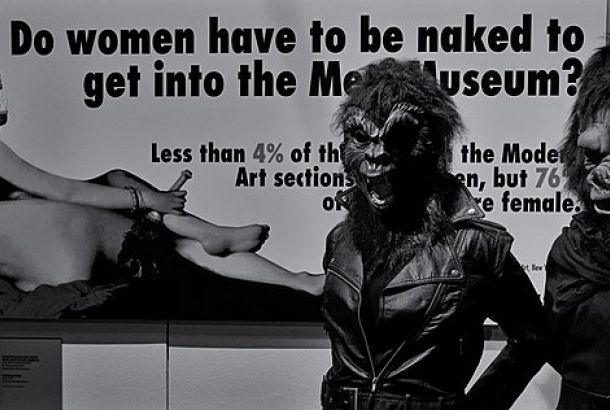

The focus of this exhibition is a collection of studio portraits, actors’ head-shots, postcards, and book illustrations. Combined, this collection unsettles the context of the original photograph.

By splicing dissimilar imagery and weaving them together, these collages communicate a mood of distortion and evolution.

In the space provided by the Whitworth, a sense of interruption was certainly felt. With nothing decorating the walls and the space, save the portraits themselves, it crystallised this pause.

The act of taking a photograph preserves a piece of time within an image, and this was communicated in the exhibition room — time felt as though it was on hold.

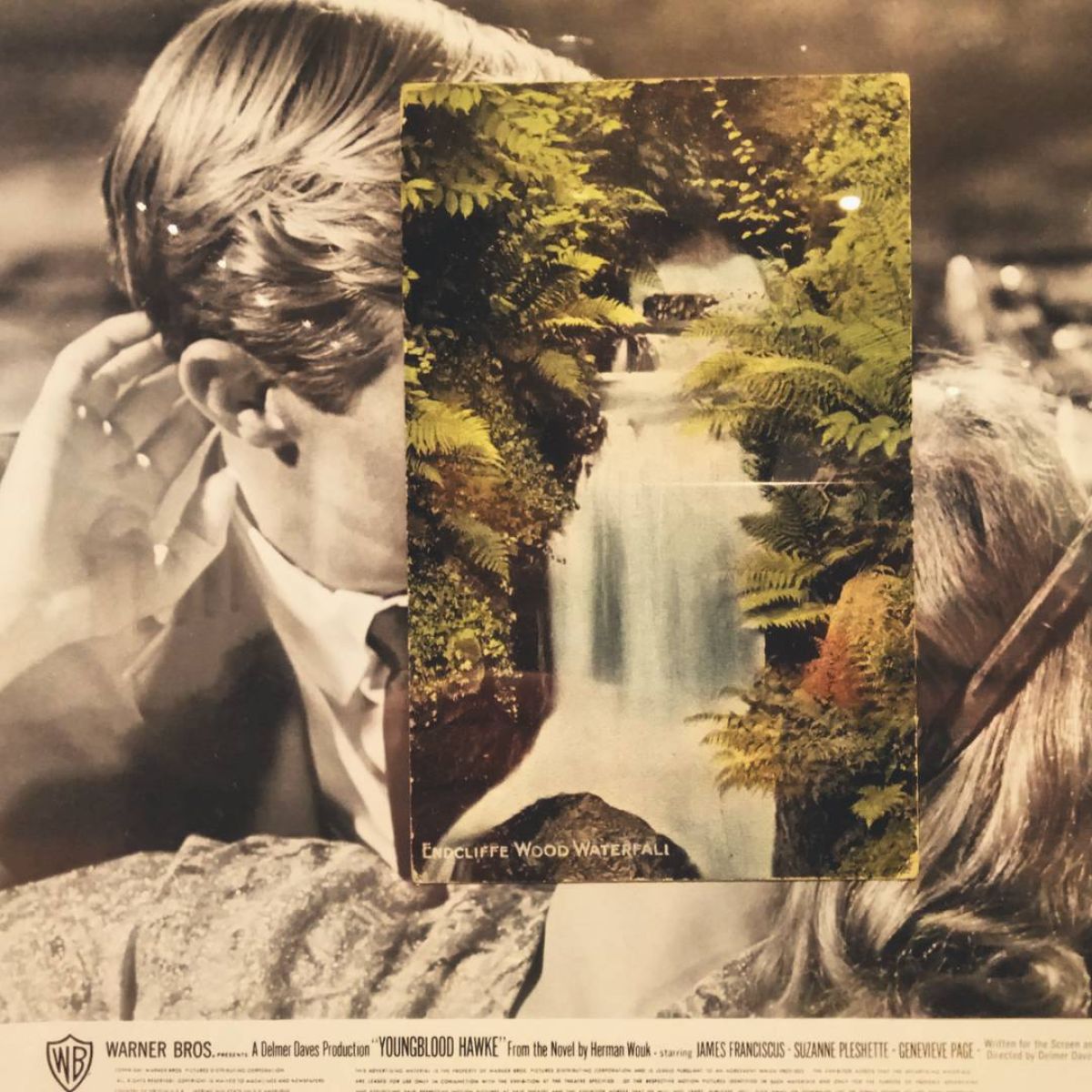

Though it initially appears to be a random collision of imagery, Stezaker’s work is incredibly precise — there is method in his madness. Each collage is linked, starting with the original image and through to the secondary image.

These collages force the pictures to evolve in conjunction with each other, as Stezaker’s use of them imbues them with a new life and purpose.

By organising the imagery in this manner he creates a sense of renewal within the frame, a studio headshot being innovated from its original purpose.

This theme of renewal is most evident in images such as Mask XII (2005) that features a landscape picture of a bridge paved across an actors’ headshot.

The positioning is purposeful, the two arches within the bridge resemble that of the eyes when combined with the man’s face underneath. The image of the actor becomes useful when combined with the landscape of the bridge and vice versa.

Stezaker’s work also contains an element of mischief. By crafting imagery in this manner his work misleads the viewer’s brain as it scrambles to find a face within a faceless image and familiarity in an unfamiliar image.

This challenge to the viewers’ brain, to find a pattern in something alien and unrecognisable, creates a communication between the artist and the viewer through the medium of his creation.

In an article in The Guardian, Stezaker commented on the unnerving nature of cutting through a photograph — likening it to cutting through flesh, and perhaps that is why his work is so surreal but so enrapturing.

The viewer is hooked by the interesting and unusual image that contradicts the assumed rules of a photograph. But this is refreshing as it serves to challenge the viewer, forcing them to analyse and understand Stezaker’s work.