Testing for cancer with nanoparticles

By Ruhi Walsh

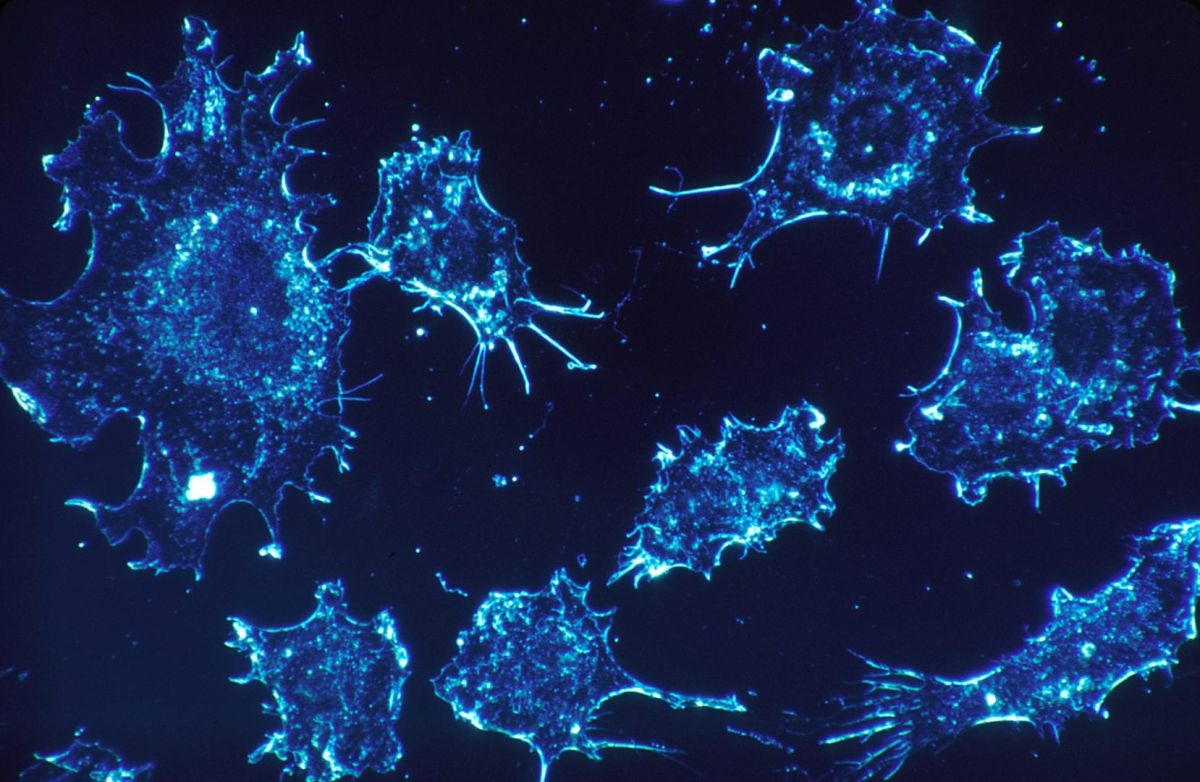

Researchers at the University may have just opened a door into early cancer detection. A joint paper between the Nanomedicine Lab and the Manchester Cancer Research Centre found that nanoparticles can be used to harvest proteins from blood circulation for analysis allowing clinicians to identify cancer biomarkers.

Blood from six patients suffering from advanced ovarian cancer was used in this study to illustrate, for the first time, the potential applications of nanoparticle forming protein coronas. Up until now the protein layer, protein coronas, that form on the surface of nanoparticles when they come into contact with biological fluids were seen as a nuisance by researchers.

Different proteins bind with varying affinity to nanoparticles resulting in coronas of different lifetimes and stabilities. It is therefore essential that the type of proteins associated with specific nanoparticles are understood before investigations occur. However, many reports have demonstrated that protein coronas differ between living and laboratory models making accurate predictions of nanoparticle behaviour particularly challenging.

This report changes things. Researchers found that intravenously injected phospholipid spheres were able to capture light-weight plasma proteins, even when their concentrations were below the level of detection by conventional methods. Furthermore, analysis of these proteins showed that some were released by growing cancers.

Disease markers are often hard to detect by traditional methods as they are small both in terms of particle size and quantity in the bloodstream. This can give rise to false positives or negatives with detrimental consequences for the patient and a decreased trust in the medical profession as a whole.

However, the heightened sensitivity provided by the protein corona and nanoparticle, called ‘nano-scavenging,’ allows for researchers and clinicians to develop a greater and more detailed picture of their patients. The authors of the paper are hopeful that this technology can amplify analytical identification of biomarkers in order to improve detection and ultimately form and early warning system for a range of diseases, not just cancer.

Whilst the approach may be novel, the use of nanoparticles is not. Patients in this study were receiving chemotherapy via nanotechnology. Nanoparticles have been used to delivery chemotherapy drugs since 2011, particularly for drugs that have damaging side effects or are degraded in the blood quickly.

For example, one of the first chemotherapy drugs delivered via nanotechnology was cisplatin, a compound that was used against half of all human cancers but degraded quickly and had the potential to severely damage patients’ kidneys and nerves. Prodrug forms of the compound were encased within nanoparticles and used to target specific sites within the body.

This approach was found to combat cancer more efficiently and with lower risks of further compromising the health of the patient. It would appear that the research marks the beginning of a new age of nanoparticle application in the fight against cancer.