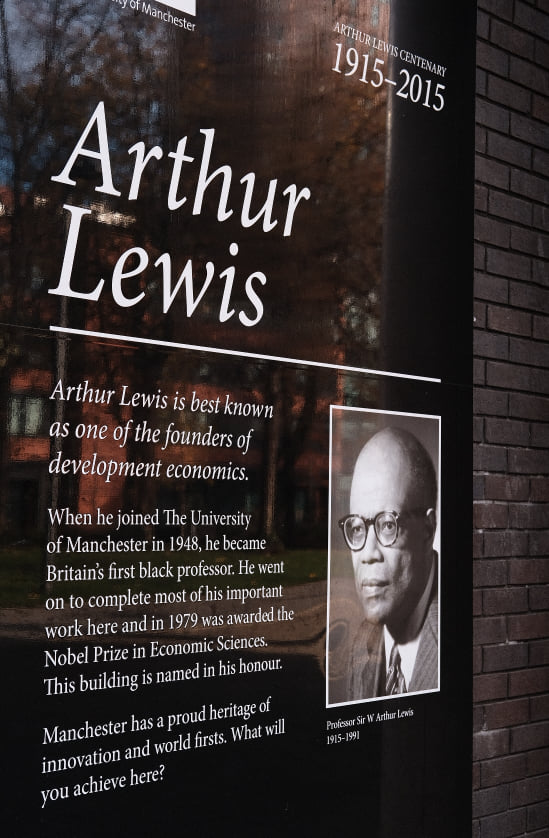

The man, the myth, the building: Arthur Lewis

By adambowles

The next in our series exploring the people behind the buildings on campus we use everyday, this time focused on the Arthur Lewis building, used for Social Sciences.

As a first-year PPE student, many of my tutorials take place in the Arthur Lewis building. But many students who sit down to have their coffee at Café Nero or browse books in Blackwell’s across the green do so unaware of the many reasons why the Arthur Lewis building stands so proudly among the other faculty buildings on campus, and the fantastic contributions Lewis made both to academic and to public life.

Upbringing and personal life

Arthur Lewis was born in St Lucia in 1915, and completed his secondary education by the age of 14, despite facing hardships growing up, such as his father dying when he was seven.

Lewis worked as a bookkeeper after finishing school, before winning a grant to go to the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), where, as the only Black student, he excelled and gained a first-class degree in 1937. LSE then offered Lewis a scholarship to do a PhD in Industrial Economics which he completed in 1940.

Lewis met the love of his life, fellow West Indian Gladys Jacobs, after she attended one of his talks in London. They got married in 1947, had two daughters, and stayed together for the rest of his life.

Contribution to and impact in Manchester

The scale of Lewis’ contribution to the University of Manchester, the city, and his field is profound, with economists at every academic institution learning, debating, and adding to ideas formulated by him.

After leaving LSE in 1948, Arthur Lewis became the Stanley Jevons Chair of Political Economy at the University of Manchester at the age of 33. This was impressive not only because of the young age he ascended to this prestigious position but also because it made him the first Black Afro-Caribbean Professor in Britain.

Lewis’ contribution to Manchester went far further than his papers published while being a professor at the University. In the early 1950s, during the outset of the welfare state, Manchester’s most deprived citizens were dying every winter due to their vulnerability and sickness often brought on by smog and pollution. This was an issue that was quite literally on the University’s doorstep, with Moss Side (Manchester’s most impoverished area) being a short walk away from the campus.

Despite the academic load Lewis clearly had on his plate, he felt implored to try and do something about the dire situation many were in. There was a clear link between ethnicity and wealth, and with many of the worst affected people being West Indian immigrants like himself, Lewis was determined to make a difference.

After conversing with Manchester’s City Council and the Bishop of Manchester, Lewis set out a goal to create a community centre in Moss Side with the aim of supporting and educating the community to try and lift them out of poverty in the future. Lewis managed to raise £3,000 to build the South Hulme Evening Centre which offered education, welfare, and legal help for the 2,500 strong Afro-Caribbean workforce in the area. Furthermore, after lobbying with senior members of the community, he persuaded Bangor Street Boys School to use one of their wings as an education centre.

During the 1950s, the average Afro Caribbean worker’s weekly wage in Manchester rose from £3.87 to £6.51 – a huge increase. Although this was not directly caused by Lewis’ promotion of mass education, his campaigning for more equitable chances irrespective of race clearly had a crucial impact on the community, and contributed to a general improvement of the quality of life of Caribbean workers in Manchester.

The South Hulme Evening Centre is still being used today, but for a different purpose – it is now the West Indies Sports and Social Centre, a crucial hub for the multigenerational Afro Caribbean community. I’d like to imagine Professor Lewis watching people play various sports in a centre he was integral to creating with a smile of satisfaction on his face!

Since 1943, Lewis had worked with the Colonial Office with the aim of working out a way to stimulate developing economies, a task which was especially important at the time since lots of countries were gaining independence from European colonisation. It was with this task in mind that Lewis wrote and released one of the most important economic papers of the 20th Century, ‘Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labour’ in 1954, which he later won a Nobel Prize in Economics for in 1979.

Contributions to the field of economics

In his Nobel Prize-winning paper, Lewis conceptualised his innovative theory of ‘dual economies’. Lewis realised that the classical view of economics – whether it was written by communist Karl Marx or capitalist Adam Smith – frequently failed to apply to ‘developing’ economies and was more fitting to the hegemonic economies of the West and the USSR.

The idea of a ‘Dual economy’ is the notion that in less developed economies there are two sectors: a ‘modern’ industrialised sector and a low productivity ‘subsistence sector’, with a surplus of ineffective labour in the latter, which was often agriculture.

Lewis argued that in order for an economy to develop and unlock true potential, it should try to move the plentiful supply of subsistence workers to the modern ‘capitalist’ sector, which would require a large investment from the modern sector or foreign investment. If done correctly, Lewis recognised that this could create a virtuous cycle, facilitating greater wealth in the country, improving income per worker and creating better services for the people. The virtuous cycle inspired by this paper has had positive effects across the world in improving the living and working conditions in 1970s (pre-Mugabe) Zimbabwe, Jamaica in 1961, and more recently Southeast Asia.

Arthur Lewis was recognised for his benevolence in Manchester and contribution to economics by receiving a knighthood in 1963. His impact on Manchester, both professionally and socially, was immeasurable, and he was a trailblazer in the sphere of economics but also in the development of social equality. Lewis’ talents managed to spark the start of a shift in the way economists studied ‘developing’ economies and, as the first Afro-Caribbean Professor in Britain in the 1940s, in how the nation viewed people of colour in the field of academia.

His contributions to the growth of the prestige of the University of Manchester with his award-winning papers made him an excellent academic, but his work improving the living conditions for those most vulnerable and marginalised in his society made him an exceptional man.