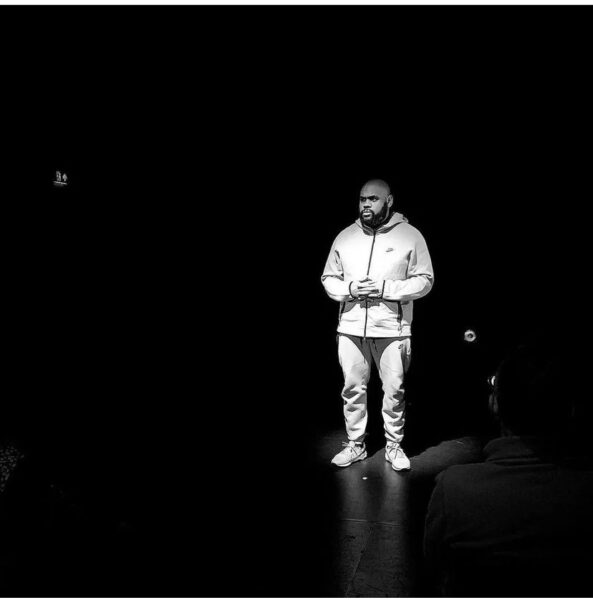

Reece Williams, who has performed his poetry across the UK and around the globe, is becoming an impactful poet in the Manchester literary scene. I talked to Williams about his debut poetry show, experiencing Manchester as a Black Mancunian, and his passion for working with young people.

Williams joined the arts organisation, Young Identity, in 2007, and within six weeks was performing on stage. He later became a facilitator for Young Identity, where he now runs weekly workshops.

Supporting young people who encounter obstacles in pursuing the arts is something he feels strongly about. Williams explains: “In the arts, in many ways, there’s still a bit of a snobbery. Working-class people don’t see themselves represented enough. I think that we need to challenge that and say, look, there are people from every single walk of life making amazing artwork, that look like you, sound like you.”

After dropping out of university in his second year of studying law, writing and attending workshops is what got Williams back on track. Since then, he’s had commissions from Penguin and The Guardian and has performed his work globally.

“I was a young person whose life was genuinely changed by starting to write poetry. I want as many young people as possible to benefit from that, because those opportunities that I benefited from were life-changing, but also they’re quite rare. I want to change that. I want to get more access to young people to give those life-changing experiences that I’ve had.”

“I think that art can make something more palatable. It can hit the nail on the head in a way that academic conversations can’t”

Williams’ workshops usually focus on Black and Asian archives. Coming from a marginalised group, Williams advocates for others’ stories to be shared where they might not be otherwise. He says, “Historically, at least, the norm has been for white poets to dominate the curriculum. However, there are poets from other backgrounds whose work is equally excellent. Their work touches on all the things that we define as excellent within literature, yet they don’t seem to get the same acclaim.” Instead, Williams explains he wants to “challenge the idea that excellent poetry only comes from a Eurocentric viewpoint.”

Relating to the workshops Williams runs, the poet argues, “We can also use poetry as a tool to educate people who come from different backgrounds, they might never have heard about a particular cultural ritual, but if you read about it in the workshop in a poem, it gets to you, and you go away and you research.”

I asked Williams if he thinks art communicates in a way that academia doesn’t. “For sure, man. If you ask the average person to go and get a textbook about the science of racism, they’re like, ain’t nobody got time for that! But if you went to a poetry slam, and somebody shared their experiences of racism with you, succinctly, in a three-minute poem, that might be more likely to move you. It’s a different avenue. I think that art can make something more palatable. It can hit the nail on the head in a way that academic conversations can’t.”

Williams has just performed his debut theatre show, This Kind of Black, at Manchester’s HOME. He describes the piece as an exploration of the Black, Mancunian, masculine experience.

“I think that’s really powerful, that idea of redemption,”

In the writing process, he was having conversations about Manchester’s history of violence. He was particularly focused on recent youth violence and knife crime, and the impact this has had on the community. “Lots of young Black men that I was speaking to felt villainised by the media because of what was happening, and it made me feel like I was a teenager again because I grew up in a town where Manchester was being dubbed as ‘gun-chester’ or ‘gang-chester’. There was a whole era of people that I know who lost their lives.” Williams continues, “I want to explore how we arrived at this place, the differences and the similarities between the symptoms of what we’re seeing then and now.”

This Kind of Black also takes a personal approach, exploring Reece’s relationship with his father, a reformed gang member. “My dad was a gang member for many years…he basically dedicated the latter part of his life to helping other young men who were walking that path to get out of that lifestyle, to turn things around. I think that’s really powerful, that idea of redemption: that we can start in one place and we can become somebody totally different with the right support and with the right mindset. There is a duality that can often happen in these things; we can’t blanket people as a bad person or as problematic when there are so many things underneath the surface that lead to the actions that we take.”

Williams grew up in Moss Side, a place he describes as a cultural melting pot, with a large Somali, Caribbean and Irish community. “It’s a place you wouldn’t particularly want to live because it was quite deprived. But equally, it developed a real sense of spirit and a real element of everything we need is here.”

I asked Reece about the intersection of his Black and working-class identities, and how this has influenced his work. He says, “The majority of my work is either personal, lived experience or collective experience while driving on peers and driving on the community’s experiences.”

The show also wrestles with being British and ideas surrounding British identity. “Because of the hostile environment that I’ve lived through, I struggle with how proud I am to say that I’m actually British. I feel like I do belong here in the sense that I’m a part of a community, a community that my grandparents and my parents built. And equally, I’m British, because my passport says so.”

Williams’ grandparents were invited to the UK from Jamaica in 1961, to help rebuild the country after the Second World War. An important part of his work is affirming the authenticity of stories from the diaspora as British stories.

Williams’ literary journey has been transformative. He reflects back by saying, “It’s been a beautiful journey. I wouldn’t be the person that I am today if I didn’t pick up a pen and write.”

In a career full of highlights, including the opportunity to perform in Australia, he has found working with and inspiring the next generation of writers to be the most rewarding part. “I think how I measure myself in ten years is not how many collections are published, or how many awards were won, but how many vibrant young, talented minds I have had a positive impact on.”