Killing consumerism: Are we headed to disposal doom?

As part of an effort to meet climate change head-on and address urgent environmental challenges with an interdisciplinary cast of experts, the University of Manchester has developed the Sustainable Futures research platform.

Has consumerism got legs?

One of the various fruits of these efforts was a recent lecture by Professor Mark Miodownik: The Albatross Lecture 2024. If you are into science non-fiction you may recognise his name from his popular book, Stuff Matters. Mark introduces his lecture as an argument for and against sustainable consumerism, asking, “Is consumerism commensurable with a sustainable future?”

Delving into the complexities of man-made materials, a circular economy, touching on the history of consumerism and taking a look into how we might manage the problems of waste and consumption, Mark asks us, as the audience, “Are we headed to a place where we aren’t going to be able to survive on this planet?” and attempts to answer the question in just one hour.

Materials, big and small

Having written a book titled Stuff Matters, Mark notes that… stuff matters. He takes the view that materials are an expression of human values. Each historical age, such as the Stone Age, the Bronze Age or the Iron Age, marks a different expression of humanity, of who we are. In summary: “We are materials, they are us and we are them.” This is a refreshing take amongst sustainability lectures which often take a more familiar (and deeply depressing) viewpoint that we, and our consumeristic desires, are doomed.

As we have evolved, innovations have led us to create ever increasingly complicated materials. We’ve moved on from wooden sticks and sharpened flint stones to micro-, nano- and atomic-scale materials. Manchester’s famous graphene is one of many scientific accomplishments which present humanity’s progress in materials on a scale which is infinitesimally small and almost impossible to imagine.

Mark highlights how we have managed, by varying and utilising different scale materials, to create multicellular-like, self-organising systems, akin to living materials. We’ve become incredibly good at doing what nature has done for billions of years – engineering on a nano, micro and atomic scale to create really complicated things. Which, “we then throw away.”

Predisposed to disposal

The UK is one of the world’s biggest waste producers, with 409 kg of waste produced per household in 2021. Mark takes us on a quick tour of history to explain how we became a nation so predisposed to disposal:

With the entry of the 20th Century also came combustion energy, steel car frames and mass production. From a time when most people had very little, mass production in the 20th century drove material wealth. Innovative machines, such as washing machines, caused a tangible change to how society worked and those in receipt of such machines became very materially rich.

But, with this mass production came mass disposal. Why bother repairing your ceramic bowl when you can simply buy a new plastic one? Why sharpen your razor when you can easily replace the blade with a new one? As well as the ease of disposability, there were health benefits to be seen from increasing the disposable market. Disposable cups which are now seen as one of the many enemies of sustainability (20-50p disposable cup charges are becoming more and more mainstream as a way to drive reusable cup use) were then seen as a way to prevent the spread of disease. This move towards disposability marked the beginning of consumerism as an economic model.

Catching up with nature – recycling man-made materials

Nature has tried and true mechanisms for degradation and recycling resources. Plants degrade, providing nutrients for soil and further plant growth. Animals die and a complex ecosystem converts their tissues to energy for other organisms to use. Humanity, on the other hand, has rapidly increased the type and complexity of materials produced but has done very little to degrade and recycle them. Instead, we have essentially tossed our trash over our shoulders and forgotten about it.

Mark admitted that it’s only in the past twenty years that he began to think about the waste he was producing as a result of material science research he was involved in, and he’s not alone. It wasn’t until 1998 that Paul Anastas and John Warner published their Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry, 28 years on from the first recognised Earth Day in 1970.

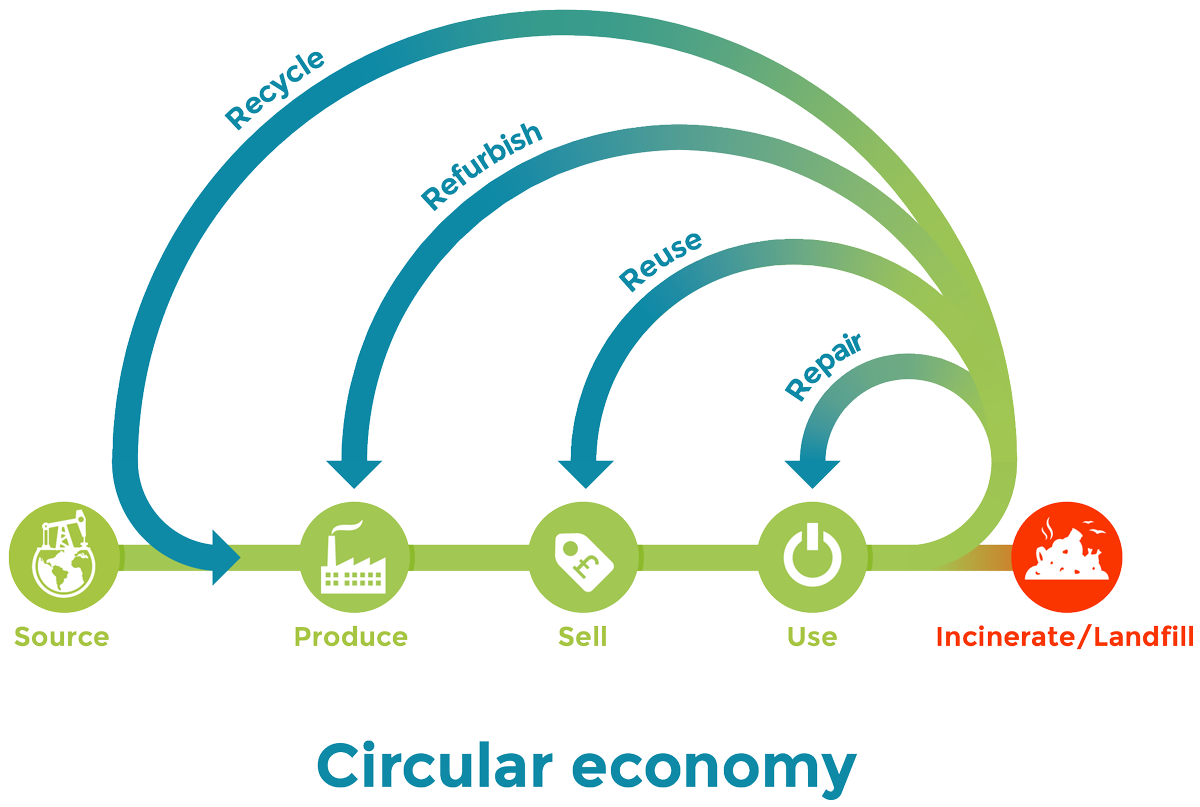

45% of CO2 emissions are from the waste we produce. Mark suggests that if we want to maintain consumerism as an economic model without causing destruction to the environment, we need to stop throwing things away. So, not a revolutionary answer but one we have known for quite some time. To do this, as the Gen-Z’s amongst us have been taught since primary school, we need to recycle, reuse and repair materials.

The only thing is.. those extremely complicated materials we produce… turns out they are not so easy to recycle. From Apple’s iPhone battery life to the lightbulb “Phoebus cartel” the rise of consumerism has come hand in hand with designed obsolescence – creating products with a shorter lifespan increases consumer needs and ultimately profits. And so our machines and devices have become increasingly more complicated (hence harder to recycle) and increasingly disposable.

Consumerism in a circular economy

As Mark puts it, we have two options. In one, “we ace recycling”. This allows for consumerism, an economic model that companies, governments and people are so fond of, to keep going. According to Mark acing recycling is something that is possible, but at best in the next 10-20 years. In the meantime, we keep consuming, recycling taxes steadily increase to pay for innovative ways to recycle, costs increase, and yet more waste is produced.

The other option is to try another type of circular economy. Instead of recycling materials we really do stop throwing things away. We put an emphasis on repair and reuse – driving jobs in local communities, drawing waste production to somewhat of a halt and attempting to change an economy based on consumerism…

But is it feasible? Repair and reuse is expensive, mass production and disposability is cheaper! With repair and reuse, will we lose innovation? Is there any way to steer multiple governments along the same path away from our current linear economy?

It seems likely that we will lean towards recycling, after all, we’ve already come some way down that road. However, whichever option humanity decides on, we know that something needs to be done for a sustainable future. The question Mark posed “Has consumerism got legs?” Well, certainly not consumerism as we know it now.