Metal Gear Solid V: Looking back through Night-Vision Lenses

By Andrew Dixon

Disclaimer—this is not a review of Metal Gear Solid V, rather, this is an analysis of the ways that a long standing series can reinvent itself in order to remain relevant and enjoyable whilst retaining its core values and themes.

I am Venom Snake, a man seeking vengeance for acts performed against myself and those I hold close. Placed in Afghanistan in the 80’s, I will use the tools at my disposal, to complete the mission that is given to me. How I shall complete this mission is unspecified; I could scout the area and mark all personnel, wait until night and then neutralise the target. I could sneak into the base at evening, place C4 explosives at the west edge of the base, crawl to the east and detonate, causing the guards to leave their posts, leaving me free to roam undetected, or I could equip a grenade launcher, call in a support chopper and just blow the place up. This freedom is unparalleled.

That was a retelling of the first few hours of my Metal Gear Solid V playing experience: the Phantom Pain (2015), and it started to make me think about the ways that a series such as Metal Gear Solid can reinvent itself to successfully uphold its principles while also reinvigorating the genre. In order to understand this, I shall look at the history of Metal Gear Solid and the ways that it has reinvented itself.

Starting with the original Metal Gear Solid (1998), the player is separated from the action, peering over with a top-down perspective. This allows the player to see beyond Snake’s field of vision. The perspective creates simple-to-understand stealth mechanics, and while the game is 3D, the depth of field perspective is not utilised as much as it could have been (a few tricks with laser alarms and cover), this however does not detract from the quality of the game. Following on from this, the second Solid title – Sons of Liberty (2001) – changes little in terms of gameplay but narratively it takes big strides. Players expected to be playing as Solid Snake, the original protagonist, and indeed, returning players begin as their hero on a tanker, being face to face with the newest Metal gear (Ray). Yet, this dream’s curtain was lifted and instead, players were presented with Raiden, a rookie on his first mission within the Big Shell. The reception from fans could be comparable to the reaction to Nintendo’s reveal of the Legend of Zelda: Wind Waker (2002)—outrage. However, the genius of this role reversal was noted. In taking the expectations of now experienced players – who began with Snake – they now have the ability to take the role of a rookie once more and achieve feats that Raiden should be incapable of doing. The unacknowledged relationship between player and character became more pronounced this way.

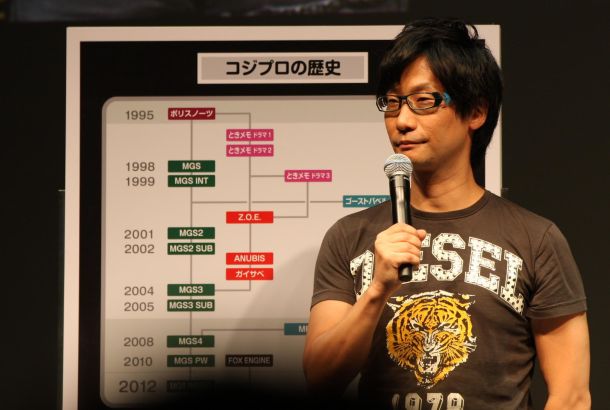

Photo: Konami CorporationI shall call the first two games Act One. Act Two, then, must contain Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater (2004) and Metal Gear Solid 4: Sons of the Patriots (2008). These games offered a third person perspective and created a greater cinematic experience, focusing on elements you could see in the field. Snake Eater offered the option for a top-down perspective, but due to not being within an environment where looking around corners was emphasised to the same extent as in previous outings, this perspective was of little use. The camouflage system of each, and the mix of urban and jungle environments brought us, as players, back to basics, and we had to evolve the methods we had engraved into our minds. These two games offered a new generation of what stealth games are and, once again, like with the switch between the Act One games, narratively we were faced with an incredible and unexpected twist – Old Snake. The hero we love, now aged and dying, but still fighting. This caused an emotional experience from the player, since we had been missing out on what would seem to be years of his life (why did we never engage with the missions that Philanthropy engaged on?). But seeing the state of our hero, unlike any other in games since, was a refreshing Kojima twist.

And now we reach Act Three. The overlooked Peace Walker (2010) and both Metal Gear Solid V games: Ground Zeroes (2014) and The Phantom Pain. Peace Walker offered a distinct change, being designed for the hand-held device—Sony’s PSP. Including a new mission system, a mother-base and more RPG elements from the characters whom you recruit, it was created on a system that was not as technically impressive as the others; however the game had more depth than some of the most complex games in the series. The HD move to PS3 is where I originally played it. Being able to redo missions in order to get that S-rank finally forced me (usually a MGS pacifist) to use weapons that killed. The game was a pleasant surprise, one that I initially overlooked because it did not have a numbered title, or originate on a home console.

Then Ground Zeroes appeared, and visually it was stunning. Rain and other environmental effects directly affected the visibility of the guards. The lighting and wind effects presented new levels of cover and affected the risk of being caught by your opponents. The game was concise, made primarily to catch people up to speed so no time would be wasted in The Phantom Pain in retelling events or explaining game controls. Ground Zeroes is a prototype. It helped to encourage the concept of engaging with a mission however you so wished, but the scale compared to the newest title is minuscule. The Phantom Pain, while only a few hours in, has slightly shifted the formula but remained truly a Tactical Espionage Action game in ways that I had hitherto not considered. From what I have experienced, Phantom Pain has opened up the closed doors of the Metal Gear Solid series to newcomers by offering freedom in its game-play and thus making it the crowning achievement of the series to date.