Socially engaged art: the feminist genre of change?

By Bella Jewell

On a trip conducted by Union Jewish Students (UJS) named Bridges not Boycotts, a group of UK students visited Israel and Palestine. The aim of this trip was to illuminate both Israeli and Palestinian narratives, and to humanise a conflict which often transcends understanding.

Having met with politicians, journalists, and activists throughout the tour of the region, one narrative stood out for me: that of the feminist activist, Yasmeen Mjalli, a Palestinian-American seeking to advance women’s rights in the West Bank.

In a Berlin-themed pub in the city of Ramallah, Yasmeen presented her past and current initiatives as an activist in the West Bank, namely the ‘Not Your Habibti’ campaign, and her most recent exploit, the ‘Dear Mr Prime Minister’ movement.

In a subsequent Skype interview, she outlined the aims of her initiative: “to illuminate the taboo surrounding gender-based issues in the Arab world through public and grassroots discourse, and secondly to create a safe space in which women can discuss these ‘taboo’ issues.”

The issue of women’s rights is often overlooked when considering the discourse surrounding the Arab-Israeli conflict: a delicate issue which has been the subject of international debate since the creation of the State of Israel in 1948. In fact, Mjalli admitted that “we [Palestinians] fucked up and let occupation be an excuse for not rebuilding ourselves”, letting social and cultural issues be “swept under the rug.”

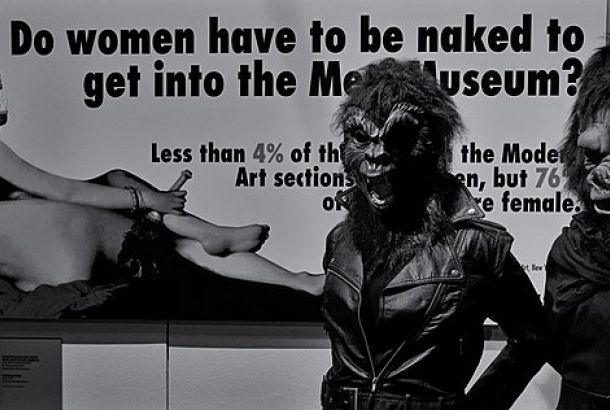

Her means of activism, however, do not manifest themselves in the usual mechanisms of protest and civil disobedience, instead, she uses “socially engaged art” to spread her message. Mjalli described how she would set up a table in Ramallah with a typewriter in front of a banner which read ‘do not stay silent on harassment.’ The hope was that women would share their stories of sexual harassment whilst she typed them on the old machine.

In Palestine, the typewriter represents a symbol of movement, as travel permits to leave and enter the country are written on these machines. By using typewriters in her work, Mjalli creates a “sort of psycho-social permit allowing women’s freedom throughout the streets”, free from harassment.

When discussing feminism’s position in Arab Culture, Mjalli claimed that in Palestine the sentiment is that “if you are harassed you must be unrespectable” in a Nation in which domestic violence is ignored, and ‘honour killings’ often go unpunished as “the law is behind the husband.”

Despite cultural barriers, Mjalli is an advocate of intersectional feminism, claiming that “whatever shade of feminism you follow, it needs to exist and have a platform” even when it doesn’t conform to the ‘westernised white feminism’ that dominates in the UK and US.

Mjalli’s most recent campaign, ‘Dear Mr Prime Minister’, pressurised lawmakers to introduce the ‘Women and Children’s Act’: legislation which would provide greater legal protections for women from domestic violence. Mjalli collected 60 letters from both men and women, calling for a change to the status quo.

Given the announcement on the 5th February that the Ministry of Women’s Affairs in Palestine was close to finalising the ‘Family Protection Act Against Violence’, Yasmeen’s project is a driving force in raising grassroots discourse and awareness surrounding the law.

Whilst miles away from the West Bank, Manchester is no stranger to the ‘socially engaged art’ that Mjalli advocates. Protest art is a key feature of the Mancunian identity given its history of activism, highlighted by the ‘Cities of Hope Street Art Convention’ of May 2016.

The Convention showcased politically driven murals throughout Manchester. The People’s History Museum’s ‘NOISE: The Art of Protest’ competition in 2013 was another Manchester-based initiative which fostered art as a vehicle of political and social dissent, which was launched following the Manchester Riots of 2011.

Living in an environment with a legacy of political activism, it is easy to take freedom of speech for granted. What makes Mjalli’s project ever more potent is her brazen defiance in the face of a Government which limits freedoms, having not held elections since 2006. In the West Bank, it is necessary to apply for a permit to carry out public campaigns, which Mjalli admitted were a hurdle which she overcame by making her applications “sound flowery and nationalistic.”

In fact, Mjalli claimed that she has been “harassed by policemen” when carrying out such events, which occasionally “have had to be cut short due to the police.” Mjalli dryly remarked in a Skype interview that often this is due to a perceived ‘threat’ these feminist events pose to “a fragile male ego.”

Mjalli’s conceptual activism provides hope and an outlet for frank conversation for women who continue to live as the ultimate ‘Other’. Despite the “inextricable presence” of the partition wall and the perpetual toxicity of discourse regarding occupation, Mjalli is determined to shine a light on women, bringing forth personal narratives to highlight the scale of endemic sexism.

You can support Yasmeen’s initiatives by checking out her website: https://www.baby-fist.com/ or liking the page ‘Baby Fist’ on Facebook.