Ludonarrative dissonance: the developer’s paradox

By Jeremy Bijl

‘Ludonarrative dissonance’ means when the gameplay mechanics (from the latin ‘ludo’ — to play) of a game are not in harmony with its narrative — its story, message, and aesthetics.

The term first emerged in reference to the game most often used as the poster-boy for viewing games as an art form: Bioshock. In a 2007 blog post, Clint Hocking, a former creative director at LucasArts, wrote that Bioshock promotes self-interest through its gameplay whilst simultaneously promoting selflessness through its story.

By giving the player the choice to choose between sparing/killing the ‘little sisters’, Bioshock offers ludic freedom to choose between altruism/objectivism, but by denying the player the choice of choosing between Atlas/Ryan, narrative freedom is withheld by the design of the game. Hocking argues that, in this way, Bioshock violates its own “internal consistency.”

If that sounds complicated, that’s because it is. More recently, however, the much-maligned Star Wars: Battlefront II offered a somewhat less obfuscated example of ludonarrative dissonance.

At one juncture in the story, Iden and Meeko, two of the game’s main protagonists, become disillusioned with the empire after it refuses to protect the citizens of one of its planets, instead choosing to save only high ranking officials.

The righteous indignation of the pair, though, is almost made a mockery of by the gameplay that follows. In escaping the clutches of the evil empire, you, the player, are made to shoot your way out by means of killing literally hundreds of stormtroopers whilst using an AT-AT to plough your way through the streets of the city.

So, first we had the narrative: not all stormtroopers are the same, and they struggle with the orders they get. Human life is important to our protagonists, and they have become disillusioned with the Empire’s disregard for the lives of anyone but their own highest-ranking officials.

Then, we have the gameplay, in which the very same protagonists kill hundreds of faceless stormtroopers – nevermind what lies under their masks – who are now expendable lives made for our trigger-happy enjoyment. It’s okay, as long as the protagonists can escape the planet to save their own skins. Sound familiar?

Later on, we are introduced to Luke Skywalker, the wise, altruistic Jedi intent on saving the universe from the evil clutches of the empire. In his introductory mission, we, the player, use him to mow down hundreds of insects whose planet has been invaded. Yoda once said, “a Jedi uses the Force for knowledge and defence… never for attack.” You can see where I’m going with this one.

The problem here is in reconciling the (narratively) inherently good nature of the protagonists with enjoyable gameplay.

Herein lies the first paradox: developers must create protagonists who are in some way representative of societies values (valour, kindness, benevolence etc.), but who are also capable of doing things utterly divorced from societal sanctioning: acts of violence, selfishness, self-entitlement and reckless abandon. These characters, in this way, have to be both relatable and, conversely, a means of escapism.

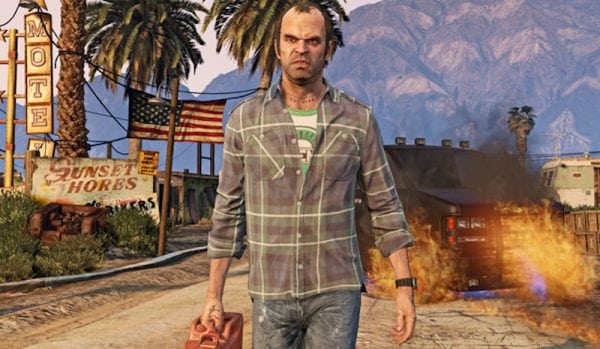

What arguably makes Grand Theft Auto V so compelling is that it simply chooses to ignore these conventions: its gameplay and narrative are perfectly blended in that it harbours no pretentions of us being good people doing bad things for the greater good but also enjoying it – it simply lets us get on with being cold-hearted, maniacal psychopaths, and writes us accordingly.

Skyrim encounters similar problems to Star Wars. In the game’s universe, we are hailed as the Dragonborn; the saviour of mankind from the world-eater, Alduin. Yet, playing the game in its entirety we kill what must be close to one-thousand NPCs (non-playable characters), and, on our way to becoming the leader of every single last faction, almost eradicate each one in its entirety.

Indeed, when I finished Skyrim after some 250 hours, I was struck not by a sense of accomplishment, but by a sense of emptiness, as I wandered around the now-barren plains of the continent. Troublingly, the only way around this, I realised, would have been to complete the opening mission and stay eternally in my house in Whiterun without triggering any of the missions.

This is a problem not restricted to Skyrim, but common to almost all RPGs. The universe of such games is so player-centric that it relies on us to trigger any given event. Philosophically, this is an issue as we become not just participatory in the fate of various characters, but causally responsible for everything that happens: Fallout 4’s waste land has a lot more life in it before we come and blow everything to smithereens (again) simply by following the directions of the gameplay.

The obvious rebuke to this is to say it doesn’t matter. The NPCs aren’t real. They have no agency. Yet is this not the very definition of breaking immersion in itself? In order to reconcile our role as the cause of in-game destruction, we must sever ourselves from the idea of the game’s universe as something we are truly a part of.

Games are, generally speaking, consumer products, inherently populist in nature. They have to be fun, playable and practical for the end-user. Whilst it would be an interesting and innovative artistic concept for Alduin to destroy the world while you were busy dicking about in some cave north of Dawnstar, it probably wouldn’t sell very well.

Yet this is where the second, ultimate paradox lies for developers. In tethering games so indelibly to the player, developers sacrifice the cold reality of an objective universe that exists outside of us rather than for us.

In other words, making us the centre of the universe – an inevitable byproduct of consumer-driven game design – forgoes the possibility for us to find our place in the in-game universe to begin with.