University of Manchester confirms September start date

University of Manchester has confirmed that the coming academic year will begin in September 2020.

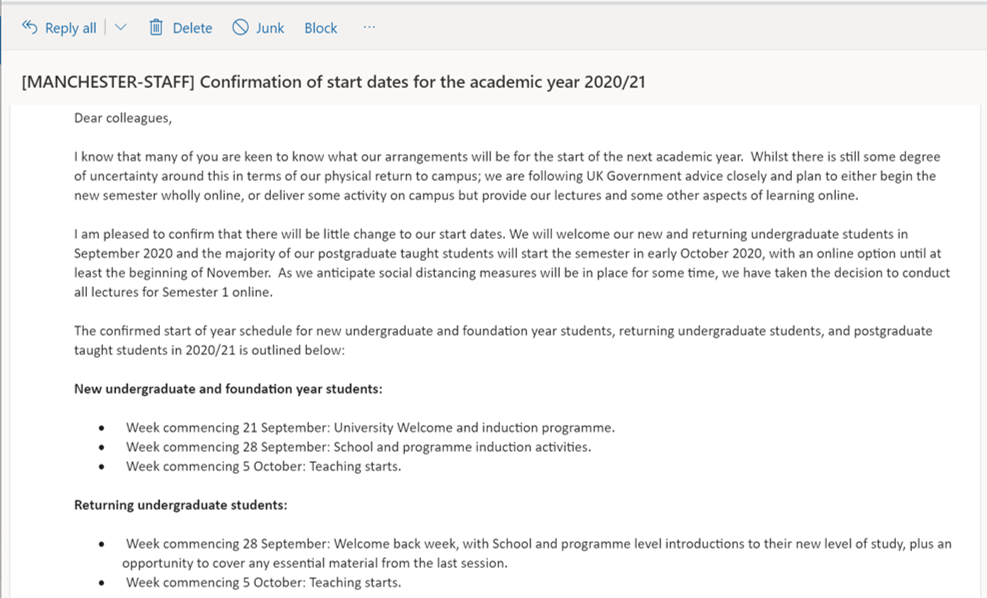

In an email sent to all current and incoming students today, the University also confirmed that teaching, particularly lectures, will continue to be conducted online to some degree after summer.

As a further safety measure, student start dates will be staggered across the final weeks of September and October, as shown below:

New undergraduate and foundation year students:

- Week commencing 21 September: University Welcome and induction programme.

- Week commencing 28 September: School and programme induction activities.

- Week commencing 5 October: Teaching starts.

Returning undergraduate students:

- Week commencing 28 September: Welcome back week, with School and programme level introductions to their new level of study, plus an opportunity to cover any essential material from the last session.

- Week commencing 5 October: Teaching starts.

Postgraduate taught students:

- Weeks commencing 5 and 12 October: University Welcome and induction programme.

- Week commencing 19 October: School and programme induction activities.

- Week commencing 26 October: Teaching starts including an online option, with an aim to begin on campus teaching activities from November, subject to UK Government advice.

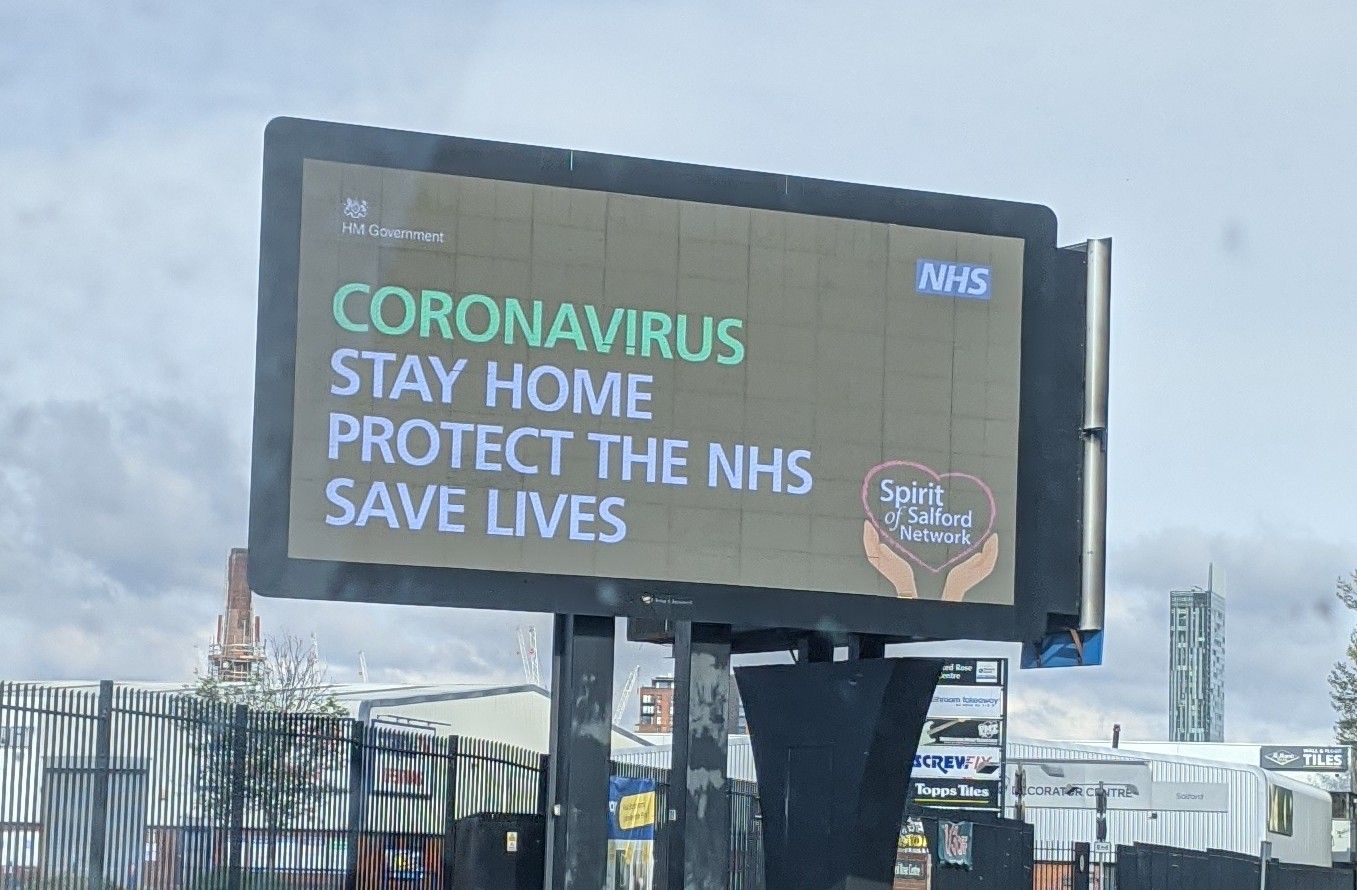

A University of Manchester spokesperson told The Mancunion: “We understand that the current COVID-19 crisis has created real uncertainty for all our students. But, as a University, we are absolutely committed to delivering the highest-quality learning and student experience at Manchester whilst providing you with the most up-to-date information.

“Our approach will be informed by the latest UK Government advice, but as we anticipate social distancing measures will be in place for some time, we have taken the decision to conduct all lectures for Semester 1 online, as a lecture theatre environment does not easily support spatial separation.

However, the University also offered reassurances that, despite plans for a partially online start, they were “keen to continue with other face-to-face activities, such as small group teaching and tutorials”, as safely and as early as possible.

Emails sent out to new Undergraduate, returning Undergraduate and Postgraduate Students detail plans for “an extended and enhanced period of induction” for new students, including an emphasis on study skills, “academic community building” and English Language support for international students.

“Welcome and development activities” are also planned for returning students. According to an email sent out today by Professor April McMahon, Vice-President Teaching, Learning and Students, these induction sessions will be “an opportunity to cover any essential material which you may have missed during the last session, as well as a range of activities and workshops that go beyond your core curriculum.”

In regards to University accommodation, UoM have announced that contract terms are being “adjusted to provide maximum flexibility for any further disruption that may occur during your time in Halls”. Further information on this is yet to be announced on contract terms but new and overseas students have until August 31st to apply for a place in halls, and more information can be found on the accommodation website.