Getting down to the art of it

By Annie Dabb

The art industry is simultaneously diverse and elitist. With that in mind, I spoke to some of my artist friends, all studying a range of subjects at different universities, about their work in relation to current global issues. Our discussion broached topics of determination and artistic passion, as well as discrimination, cultural appropriation and underrepresentation.

To these creatives, art just “made sense” as a natural progression. For Georgia, this took the form of rejecting what schools classed as ‘fine art’ – “the very opposite of fine art” – whereas Ryan rejected the stereotype that men should be sporty rather than artistic, and Lucie the “fashion girl” characterisation, Phyllis entered the art world via an unexpected course change from law to drama and Niamh from a self-confessed tendency to be a “drama queen”.

Media and messaging

As they developed their practise, their chosen media evolved. Ryan compared the photo realism expected of him in school, which had him painting portraits onto actual doors, to the more flamboyant textiles and prints he produces now, laughing about the “dick print” he’s working on. Georgia also painted school as limiting, the grading system giving her a validation complex in relation to her art. She rediscovered her love for “film, photo and writing” at university and spoke about the ambiguity of her art, speculating that “by not being overtly politicaI, I guess I am being political at the same time.”

The drama students discussed the transgressiveness of their practice and the idea that drama has less physical production value than fine art or textiles. Niamh cast art as a mode of storytelling, proclaiming “we’re not being ourselves – and that’s the point.” Whereas Phyllis, who prefers directing to acting and in fact hates monologues, described her degree as a process towards an end goal; using applied theatre to “tell a story but to bring it out of someone else.”

Lucie’s constant questioning of the ‘why’ behind her own work conveys art as all-encompassing and she is quick to dismiss the “social construct that creative subjects don’t lead to anything” because “it’s not taught to lead to anything.” With Lucie’s emphasis on “questioning our practice”, as well as Georgia’s challenge to the “pessimism around creative subjects”, both artists combat enmity towards their industry.

Lucie’s current work combines West African prints with William Morris patterns. In a way that would have Wordsworth running for the hills, she and Ryan denounced the use of flowers in their work with a swift “fuck floral”, disregarding pastoral print as boring and predictable.

Discrimination and exclusion

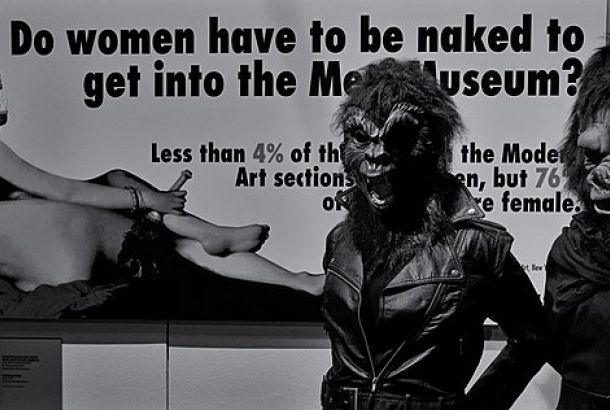

It is saddening that even in the art world, given gay icons like Keith Haring or David Hockney, everyone in the group has experienced their work being stereotyped in relation to their gender and/or sexuality. Lucie highlighted the lack of representation of BAME (Black Asian Minority Ethnic) artists or, what is worse, the expectation that they produce cultural work in line with society’s expectations of a “black creative”.

We were shocked to learn that there are only six black students across Lucie’s, Phyllis’ and Niamh’s courses combined. Lucie explained how caucasian audiences tend to view African art through a Westernised lens and dismiss art that doesn’t fit such categories by a person of colour as “not African.” She is reluctant to personalise her art because of the difficulty involved in conveying her culture to a (perhaps wilfully) misunderstanding white audience. She even refrains from putting her face on her portfolio as “that in itself would change the interaction with the company or designer.”

Nodding somberly, we realised how different Lucie’s experience is as a person of colour; the underrepresentation and fetishisation of herself and her work in a society which simultaneously discriminates against and extorts, through cultural appropriation, the art of non-white or BAME artists.

Creating during Covid

Covid-19 has all but stagnated the art scene, so it was little surprise that Ryan was concerned that his lockdown portfolio may be taken less seriously than that of someone with full access to resources and studio space. However, Phyllis and Niamh were somewhat consoled to know that the study of drama online is uncharted territory for everyone. Thus, a prospect that was initially daunting and isolating led them to develop an entirely new skill set. For example, it has prompted Niamh to start writing monologues.

Georgia was also optimistic about the effect of the pandemic on her work, seeing the potential for art to reflect current events as the Renaissance period did for 14th-century Europe. Lucie suggested that artists today are the only ones in history to have experienced the coronavirus, making their work unique and therefore desirable. She also noted our inevitable movement into a post-digital age, which emphasises technological mastery as vital to survival in the labour market.

The North-South divide in the art world

Our discussion turned to the possible stigmatisation that comes with being a ‘Northern creative.’ At times, they have all been subjected to mockery for their accent, as well as – more soberingly – having their Northern roots overshadow conversations about which universities would realistically consider them. (Needless to say, everyone stayed in the North for their degrees.)

Despite Geordie being ‘the oldest English regional dialect’, Georgia confessed that she “always felt like [she] couldn’t be successful because of where [she’s] from.” Northern actors are consistently underrepresented or cast as stupid characters in film and media.

According to Niamh, during the pandemic “people from the North East are applying to London-based jobs…because they don’t need to spend money to go down to London”. This met with broad agreement and we had to acknowledge that art is something of a privilege due to its instability as a career option. It is far more accessible for those able or willing to go to London, with its prolific art and theatre scene – the ‘museum capital of the world’.

Ferne Arfin has described Newcastle’s demotic as a ‘difficult dialect’, suggesting that ‘most Brits are puzzled by it.’ We laughed at the ridiculousness of expecting that ordinary people sound like privately educated Radio 4 presenters and Niamh jokingly suggested that people who can’t understand her “put a fucking subtitle on [me]” but class still plagues the industry.

Questions of prestige

Lucie passionately deconstructed the hierarchy within art which effectively situates her degree ‘textiles and design’ below ‘fine art’, the latter residing obnoxiously at the apogee of art. As a student of the latter, Georgia was quick to interject and to endorse mass-produced art.

Everyone in the group had experienced some degree of rejection or sacrifice to get where they are now. Lucie, for instance, lamented her choice to attend an art-specific university, and felt she had missed out on mixing with a more diverse range of students in exchange for a more credible artistic qualification.

Pride in one’s work

Georgia revealed that much of the work she has produced she hates. Routinely, she will get bored with a medium within a matter of weeks and be eager to move on. Nevertheless, she finds continual joy in her writing, a process which sometimes consists of creating a whole scene just through listening to one song over and over.

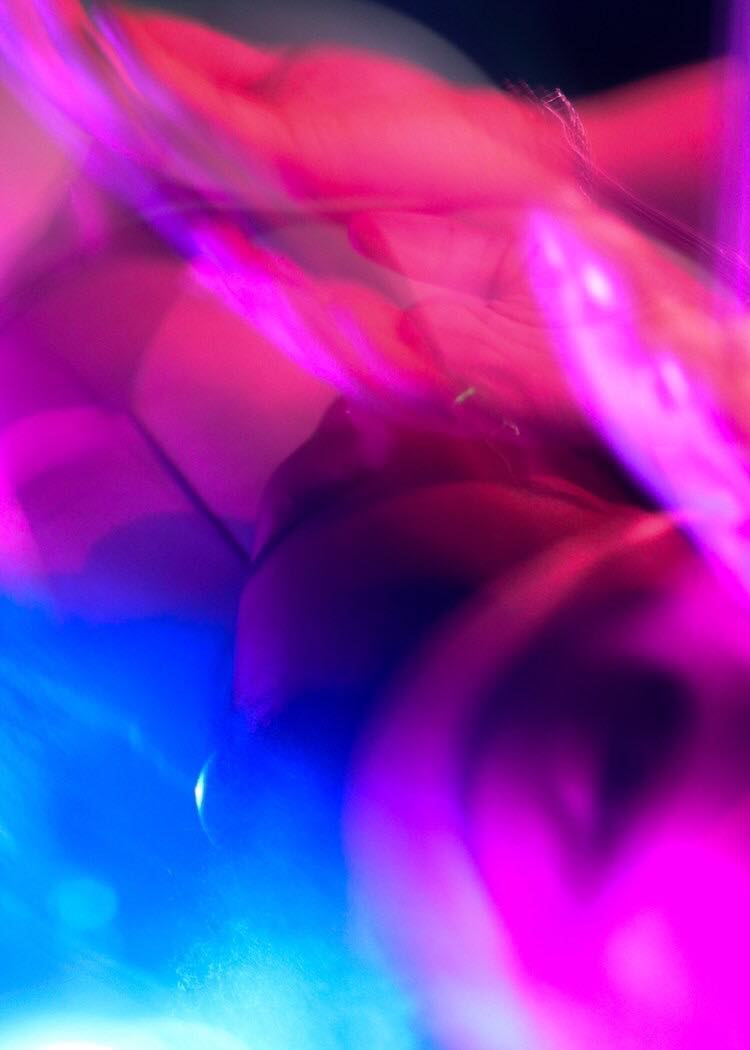

Lucie showed us beautiful intimate photography, blurred shots depicting vibrant colours and sensual movement. Whilst captivating, Lucie’s description of the photos as “so distorted that it’s not even me anymore” speaks of the distance she places between herself and her work. This is largely due to her fear of cultural misappropriation and being judged as a queer woman of colour instead of an artist in her own right. Our conversation closed on the ongoing importance of decolonising the arts.

I am bewildered by the complexity of the art industry and of the lives of artists. But I am also inspired: these young creatives have perceived the pandemic not as an impassable hindrance but as a life-changing moment in history.

Far from the stereotype of brooding, self-centred, mysterious artists, these are a bunch of lovely creative people. They navigate the minefield of the art world through self-expression and continually searching for how best to, as Lucie put it, “communicate complex ideas through a beautiful, simplistic practice.” It’s my privilege to know them.

Special thanks to:

Lucie Turton @lucie.a.t

Georgia Brooks @oneartist.gia

Ryan Whitfield @ryanwhitfielddesign

Niamh Euers @stiamhs_achiamhments

Phyllis Hoyle

For a longer version of this article, see here: https://avoidinganannieyurism.blogspot.com/