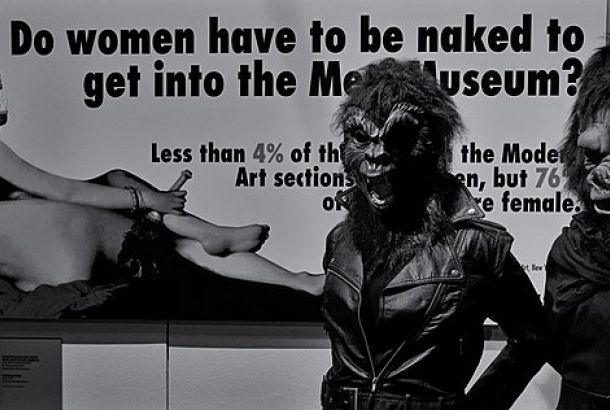

Manchester Art Gallery and decolonisation: Has it been successful?

On a Saturday afternoon, Manchester Art Gallery is teeming with visitors, young and old. They find retreat in its homely café or marvel at its beatific grand entrance, spiralling into a gorgeous classical ceiling. The magnificent building holds one of its latest exhibitions, Rethinking the Grand Tour, which shows the interaction between travel and Renaissance Europe and how it extends to the colonised world.

The Grand Tour was the custom of taking a trip around Europe, mostly by men of the British nobility, between the 16th and 19th centuries.

“Beneath the refinement of the Grand Tour is the story of empire and cultural appropriation,” reads a bold-lettered yellowing sign at the entrance of the exhibition. It continues stating, “as the scope of European tourism extended to the Middle East and Asia, a colonial viewpoint prevailed.”

But how well does the Gallery’s exhibition confront the past?

In an attempt to reassess the Grand Tour, the Gallery has selected four contemporaries to respond to its colonial legacy of it (alongside various classical pieces from Greece and Rome). They are Khalda Alkhmiri, Mahboobeh Rajabi, Kani Kamil, and Kofo Kego Oyeleye.

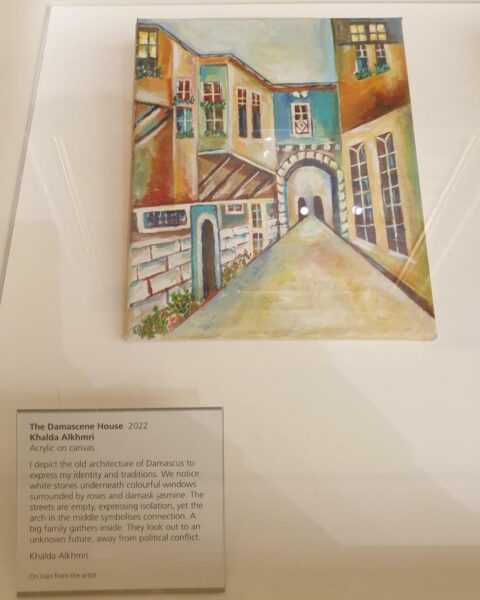

Khalda Alkhmiri stands out with ‘The Damascene House’, a painting depicting a colourful street and traditional architecture from Damascus.

At first glance, the painting is void of people, which, as Alkhmiri explains in a note, is to express isolation, within the scene, from political conflict. The painting has powerful symbolism, such as the archway, used to show human connections in times of uncertainty. Alkhmiri’s brushstrokes effectively portray a reclamation of Syrian identity during conflict and moments of loss.

Mehboobeh Rajabi offers a poignant exploration of her individual experiences of claiming asylum and the tumultuous emotions that come with being displaced.

She focuses on the piece ‘Swan Lake’, a vibrant artwork with reflective hues of green and shades of blues, backed by swirling shadowy scenes – a work encapsulating the feeling of being lost and becoming a displaced victim of colonialism.

Alongside this, Kani Kamil gives a voice to Iraqi Kurds, represented through the boxed display of the Hashmi dress her mother once wore. She notes down the nostalgia she feels and the sense of empowerment in offering visibility to “unseen pieces that have been brought to this country by Grand Tourists.”

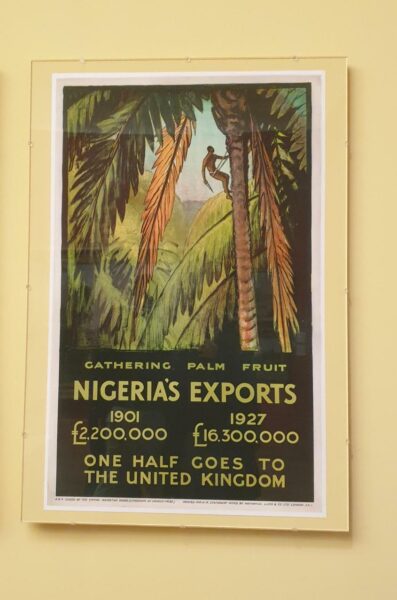

Lastly, Kofo Kego Oyeleye’s commentary on colonial displays: “Nigeria’s exports” and “A N**** Fisherman”, plastered in loud letters accompanied by outdated and racialised images of Nigeria and its society.

Unsurprisingly, it is the most shocking of all the exhibition pieces, as it was commissioned by the Empire Marketing Board (a body created to promote inter-Empire trade). Oyeleye rightly comments on “the oversimplified manner, typical of the Grand Tour’s colonial perspective.”

He explains, “if there was an opportunity for growth, people within Africa would have no reason to migrate.”

The exhibition is all about travel, and how the empires contribute to modern displacements. All four contributors have presented powerful testimonies about the legacy of colonialism. But does it quite achieve its mission of decolonising narratives about the Grand Tour?

The exhibition is an ambitious display, but are four distinct voices enough to fulfil its approach of decolonisation?

Take the British Empire, which once owned nearly a quarter of the global population. When considering the entirety of international displacement that has come with the legacy of the Empire, choosing to display only four voices, despite the worldwide spread of the empire, can start to feel tokenistic.

Is the ambition reflected fulfilled?

Alkhmiri, Rajabi, Kamil, and Oyeleye offer valuable contributions to the exhibitions, and there is a case to be made to expand the exhibition and include more voices, and artworks, that show the global story of colonialist travel.

But Manchester Art Gallery does clearly show the intent to create a space for the diverse local community and acknowledge the colonial past it has, beyond the Grand Tour Exhibition.

“We acknowledge that our origins are entangled with colonialism and capitalism and that our prosperity and collections were built on manufacture, trade and empire,” the Gallery said in a statement. “As a civic institution, we are critically asking whose and what narratives are on display.”

To their credit, the Gallery offers a wide variety of displays that aim to represent the local population and readdress its colonial past, such as the Trading Station, revealing the colonial history between tea and other drinks and slavery. Or other incredibly insightful creations such as ‘Uncertain Futures‘ which aims to represent a collective of local Manchester-based women and understand how “gender, age, labour, class, migration status, disability, and race impact women’s paid and unpaid work.”

Manchester Art Gallery has put in an immense amount of effort to move towards decolonisation beyond Rethinking the Grand Tour.

However, one does notice details around the gallery which may question whether the Gallery has wholly executed its ambition to decolonise: on a light blue wall, encased in a faded golden frame, is ‘The Coffee Bearer’, by John Frederick Lewis, not included in the Revisiting the Grand Tour exhibition.

At first glance, the painting is a well-detailed piece, featuring a dark-haired woman in beautiful robes. Yet the accompanying sign next to the painting describes Lewis as having “adopted oriental robes and recorded life in crowded bazaars and harems.” Ironically, his pictures are portrayed as “faithful reproductions of Egyptian life.”

John Frederick Lewis was a member of the Oriental Arts Movement, which strengthened stereotypes that the wider Arab world was lesser than the Western world. The movement fetishised the East and produced paintings for commercial use. Lewis exploited Egyptian culture and racialised the painted female coffee-bearer to produce commercial works.

There is no acknowledgement from the displays that this artwork itself is a racist and exoticised piece, an oversight that doesn’t appear to meet the target of fully acknowledging problematic artwork.

Another instance which presents another ambiguous display is an oil on canvas called ‘The Water on the Nile’ by Frederick Goodall. It shows “the exotic lifestyle” and how the artwork brings out the “brilliance of the Eastern Landscape.”

Perhaps the presence of the exhibition on Revisiting the Grand Tour and displays of similar sentiments must be celebrated with a pinch of salt, but nonetheless celebrated. Evidently, the intention is clear in readdressing the impact of the Empire, and the exhibition is a refreshing take, albeit with smaller errors of problematic labelling.

It is premature to denounce the Gallery as performative, as it showcases contributors in an attempt to decolonise the audience’s gaze. The improvement lies in addressing signage and including greater representation in its exhibition Rethinking The Grand Tour.

One thing is clear. The Gallery, with its impressive exhibitions and displays, is not without imperfections. For now, the Manchester Art Gallery, along with creative and educational spaces more broadly, can do more to challenge old colonial-era mindsets but has provided a solid foundation to work on.