“A duty to stand in solidarity”: Peter Tatchell on his LGBTQ+ activism

By oliverclegg

Peter Tatchell, now 71, has had the kind of spectacular and radical life that seems like the stuff of fiction.

He was a prominent member of the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), helping to organise the UK’s first Pride in 1972. He went on to be a founding member of OutRage!, which used bombastic direct-action protests to fight homophobia.

Originally from Australia, he has lived in the UK most of his life. He stood as the Labour parliamentary candidate for Bermondsey twice in the 1980s. In 1991 and again in 2001, he attempted to perform a citizen’s arrest on Robert Mugabe, the former President of Zimbabwe accused of human rights abuses.

He has continued to campaign for LGBTQ+ rights, most recently making headlines after he was arrested in Qatar for calling out the regime’s bigotry before the 2022 World Cup.

Tatchell remembers the homophobia of the 1970s saying “Most aspects of gay male life remained criminalised, despite the partial reform of 1967.”

“Lesbian mothers,” he continues, “had their children taken off them by the courts. Gay bashings and arrests were rife. Our community was targeted for violent attacks by far-right extremists like the National Front.”

Media coverage of LGBTQ+ issues, he tells me, was almost non-existent and when it did happen it was nearly always viciously homophobic. “Parliament was so homophobic that MPs refused to even discuss LGBTQ+ rights,” he says.

Of course, this bigotry didn’t dissuade Tatchell one bit, instead motivating him to fight back. Tatchell joined the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) and says the organisation “put LGBTQ+ rights on the public agenda and transformed LGBTQ+ consciousness, from shame to pride and defiance.”

“For the first time, thousands of LGBTQ+ people came out and protested against our persecutors. GLF’s ‘Gay is Good’ slogan challenged the centuries-old view that being gay was bad – and mad and sad. This was at a time when most LGBTQs were closeted and ashamed.”

GLF founded the first LGBTQ+ switchboard and the first LGBTQ+ community newspaper, Gay News. It also established the first counselling service run by and for LGBTQ+ people, called Icebreakers. “GLF’s key demands were about liberation, not mere equality,” Tatchell explains.

“We did not seek equal rights within a flawed status quo, our goal was the transformation of society to end straight supremacism and all other oppression.” GLF used the tactics of non-violent direct action and civil disobedience, modelled on the black civil rights movement in the US. This meant, he goes on, standing “in solidarity with women, the black and Irish communities and working-class people.”

As part of the GLF, Tatchell helped to organise the UK’s first Pride in 1972.

“There was a mixed reaction,” he tells me. “Many people [showed] their disapproval while some expressed support. At some points, there was almost one police officer for every marcher. Some officers pushed and shoved us. Others shouted homophobic abuse. The Pride march was a historic milestone, but there was no coverage of the event because the British media at the time were so homophobic.”

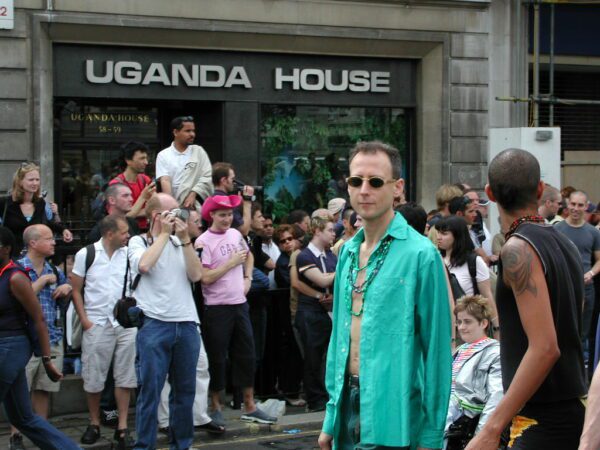

Photo: Own work @ Wikimedia Comms

Peter Tatchell was recently vocal in opposing Qatar’s hosting of the World Cup. He travelled to the Middle Eastern country to stand with the LGBTQ+ community there, which has long been oppressed by the hardline government.

LGBTQ+ people in Qatar face criminalisation, jail, online entrapment, ‘honour’ killings and forced ‘conversion’. Homosexuality is punishable with sentences that can include three years in jail and death by stoning for LGBTQ+ Muslims.

Tatchell saw showing his support as essential: “There can be no normal sporting relations with an abnormal regime like Qatar. If a star Qatari footballer came out as gay, he would be more likely to be jailed than be selected to play for his national team. That’s discrimination and against FIFA’s rules, but FIFA is allowing it to happen.”

“We have a duty to stand in solidarity with people who are being persecuted.”

The Qatari regime had little tolerance for protests during the tournament. Tatchell was arrested by the authorities after standing in Qatar’s capital, Doha, with a placard supporting the LGBTQ+ community. The placard read ‘Qatar arrests, jails & subjects LGBTs to ‘conversion’ #QatarAntiGay.’

“Police and state security were firm but polite,” he tells me. “I was detained for nearly an hour before I was released. The regime only released me because they did not want the bad publicity of my being beaten and jailed in the run-up to the World Cup. If I had been Qatari, the end result would have been very ugly. The regime does not allow protests.”

Recently, as well as advocating for human rights, Tatchell has been advocating for animal rights and veganism. He tells me of a “moral duty to stop abusing other animal species. It’s time for both human and animal liberation.”

It’s heartening to hear about Peter’s 55 years of activism, but have we really made much social progress?

In the same year as the first Pride there were fears of spiralling inflation and massive strikes by mine and dock workers. Peter doesn’t share this pessimism. He is keen to point out the incredible amounts of progress that the LGBTQ+ rights movement has made.

“Up until 1999, Britain had the largest number of anti-LGBTQ+ laws of any country in the world, some of them dating back centuries. Yet in the years since 1999, all of those homophobic, biphobic, and transphobic laws were repealed. That was the fastest, most successful law reform campaign in British history.”

Since 1999, a ban on LGBTQ+ people serving in the military was lifted in 2000. In 2001 the age of consent became 16 for gay and bisexual men. Trans people have been able to change their legal gender since 2004, although the process, Tatchell warns, is “needlessly complicated and needs reform.”

Other reforms include protection against employment discrimination for LGBTQ+ people in 2003, which was extended to housing, advertising, education and the provision of goods and services in 2007. Perhaps the most symbolically significant moment of all was the legalization of same-sex marriage in Great Britain in 2013, followed by Northern Ireland in 2020.

Considering these milestones, Tatchell sheds light on what can seem like a dark period in the movement for equality. Liberation, with all its barriers and setbacks, finds its way through the cracks.