Scorsese’s Shutter Island: Unforgiven and beyond redemption

By Aisha Zahira

There is no one who is not at least vaguely familiar with Martin Scorsese. Even those individuals who proclaim to not have dived into his filmography are aware of his cultural impact in film. With both mainstream success and critical support (though not always paired together), Scorsese has firmly positioned himself in our consciousness one way or another.

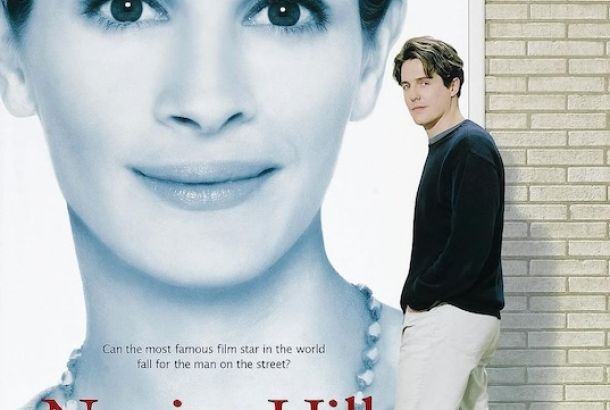

So it seems at odds with his presence to suggest he would feel regret – an emotion we would consider alien when discussing him – about any of his work. But this was exactly what was implied in a recent in-depth GQ interview promoting his brilliant new film Killers of the Flower Moon. Thirteen years after the release of Shutter Island, Scorsese suggested winning an Oscar for The Departed “encouraged me to make another picture with Shutter Island. It turned out I should have gone on probably to do Silence.”

Given this comment and a later one stating it was “the last studio film [he] made,” this article serves as a reappraisal of Shutter Island in light of Scorsese’s recent remarks.

Warning: Spoilers for Shutter Island ahead

A popular comparison of the time was made between Shutter Island and Inception, released within four months of each other. Both layer stories within stories, follow the journey of a man succumbing to guilt after the death of his wife and require the audience to participate in the character’s dream world in an attempt to come to terms with said death.

However, this serves as a rudimentary similarity, bolstered by the fact that both star Leonardo DiCaprio in the leading role. Whilst it was a good year for DiCaprio at the box office, to find a connection within Scorsese’s own collection of films, you might direct your attention to Cape Fear. A picture that infected Scorsese with ‘remakitis’, as J. Hoberman put it in a contemporary review of the 1991 thriller.

In this case, both are unsettling thrillers and, though Cape Fear employs more overt horror tropes, both are also obviously ‘pulpy’. This is to say Scorsese is somewhat familiar with this commissioned, one-for-them style of filmmaking. Positioning Shutter Island in this genre lends a greater understanding of how it does, or in this case largely doesn’t, work.

The story follows Teddy (DiCaprio) and his partner (Mark Ruffalo) searching for an island housing a mental institution for one of their escaped patients. Teddy is searching for a man named Andrew Laeddis, who was responsible for the fire that killed his family. However, it is later revealed that Teddy is actually Laeddis, and a patient of the hospital. The whole plot was fabricated for his benefit, and he opts for a lobotomy to forget his past actions.

Scorsese immediately lends his style to the film with the opening shot. The image of a ship coming out from the fog serves as a compression of the main theme of the entire film. As it enters the bay, it serves to transport Teddy to the island, but so too does Laeddis enter the island as Teddy, a beacon of his dual identity. Later on, Rachel Solando’s escape from her room coincides with her doctor’s supposed exit from the island by ship. Of course, the second-time viewer is aware that her doctor is actually the partner played by Ruffalo, again emphasising the idea of having to leave the island to come back as the fictional counterpart.

The setting of the island serves two functions: as a physically claustrophobic place (the characters move in circles, and this circularity allows them to be constantly ambushed) but also as a representation of Laeddis’ own claustrophobic mind; the internal labyrinth reflected in the external island. The institution’s senior psychiatrist Dr. Crawley (Ben Kingsley) is concerned with old vs new psychiatry. The title of the film is an anagram for Truths and Lies. These are only a few of the doubles that permeate the film. Nevertheless, the metaphor is simple and soon grows tiresome. Sure enough, it may keep the viewer searching for clues on a re-watch but is the film even worth a second viewing?

To answer this question, we can look further into the bones of the story. The film aims to incorporate various themes – the changing field of psychiatry, World War 2, Laeddis’ potential PTSD, family life, and death. There is never any shortage of thematic resonance to draw upon. Unfortunately, this all serves to build up to the final ‘twist’ of the film, that it is Laeddis who is actually a patient of the facility, and any commentary is foregone in favour of explaining away his condition. The density of the plot is just a trick. It doesn’t really matter, not while the audience is too busy being surprised by the reveal.

As thrilling as this reveal is, its extended exposition calls into mind the final scene of Psycho, a scene most feel was somewhat unnecessary and was deemed “arguably Hitchcock’s worst scene” by Pauline Kael (though she did not have any fondness for his other work, either). Understandably, Shutter Island requires an explanation because ‘Teddy’ requires one but, again, it feels as if the writers need to justify why the audience has sat through two hours of what ultimately amounts to nothing.

Similarly, the characters also act not for the sake of the story, but for the audience. The self-congratulatory form of the film always keeps in mind when the twist will be revealed and how it will appear to the viewer. Ruffalo does a good job of overacting as the doctor pretending to be Teddy’s partner, his tone often bordering on comedy. DiCaprio looks exactly as strained as the character requires, but continues to emphasise every syllable he can get his mouth around – “there’s a sixty-seventh patient, doctuh” – working very hard to always be incredulous so the audience remains ignorant of the twist. Scorsese’s encouraging camera positions Teddy as the light, unable to reflect on the darkness of the other characters.

This all leads to the film being less than the sum of its talent, and less than the sum of its parts. Its assessment of psychiatry is compressed to the palatability of a high-school classroom, and even the point regarding the treatment of patients leaves the viewer confused. After the Dr. spends the runtime waxing poetic about the need for more humane treatment within the facility, Laeddis ends up as the butt of his own joke and requiring a lobotomy – a mixed message if there ever was one. It makes sense that Scorsese would call this a ‘studio movie’ – its themes are written for the most generic audience possible.

I would love to be able to say there may have been a great film somewhere within the convolution that is Shutter Island but even that is not the case. Ultimately, even Scorsese’s guiding hand and understanding of the genre cannot save the film from itself.