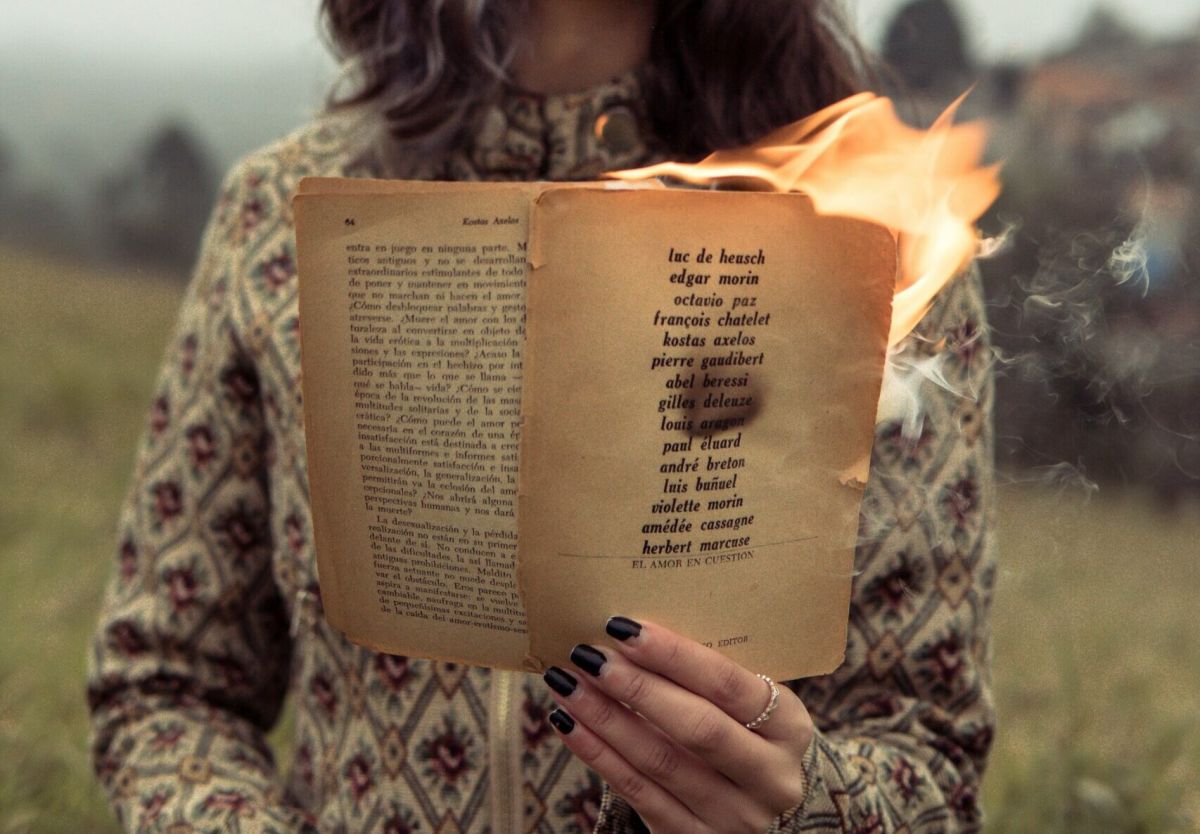

What in 451°F: How and why do book bans still exist?

By Em Tarasenko

In October Penguin Random House launched a new award for high-schoolers, celebrating the life-changing power of the written word. However, celebration in this case is just another attempt to stall a rising book ban campaign across the US. Yes, it’s a great initiative, but why do we need to have a whole campaign against book censorship in our brave new world?

Born to ban: what are the book bans exactly?

Who said the book bans are something from the dark, messy Middle Ages? There is even a Wikipedia page on governmentally banned books across the globe, and Penguin’s award is the reaction to the recent book-banning campaigns. Over the last school year, the number of bans increased by a third with 3362 cases across the US. In the long list, there are multiple award-winning and critically praised books such as The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison, Looking for Alaska by John Green, Gender Queer: A Memoir by Maia Kobabem, and Maus by Art Spiegelman. Yes, empathy is a dangerous skill to teach.

But bans are not a modern phenomenon. ‘Detrimental books’ fell into the different restricted lists at least since 213 BC in the Qin Empire. In the 20th century, things were almost the same. Books critically praised today for their honesty, like The Colour Purple by Alice Walker, were cleansed from the library shelves in the US. The award-winning critique of Soviet reality, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, was widely read everywhere except the USSR. But the last one for the obvious reasons.

Perhaps, book burning was around since the texts themselves existed in written form. Author burning policy too, but luckily the world seems to be over at least this one.

New achievement unlocked: you are blocked

No matter in historical or contemporary decorations, there are three main reasons for all the bans: religion, ethical norms, and politics. The things you don’t discuss at the dinner table. Sometimes they strike in combination, and sometimes one reason is instrumentalised for the other — like when religion boils down to traditional values, serving conservative ideas.

So how do books make it into the condemnatory list? Statistics say requirements are quite straightforward: the authors whose books were banned were ‘most frequently female, people of colour, and/or LGBTQ+ individuals’. Also, 30% of them had characters of colour or touched on themes such as race or racism, 30% represented LGBTQ+ characters, and 6% had trans characters. Some of the books also criticised nationalism and hate crimes.

In the 1980s, for example, making it to the banned list was easy. Among The Colour Purple, classics such as Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck and The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald were banned. The reason was so-called obscenity, but these modern classics simply discussed themes which were taboo in the society of those days. Perhaps, pushback from gaining new freedoms and pointing out societal imperfections are quite expected. But if so, what makes new bans different?

In the US, new book bans are followed by a wide range of changes in legislation. It’s not only prohibited to read The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison — a clever and deep novel on self-acceptance and internalised racism — in certain schools or regions, but also to teach classes on race, equality and sex education. Said to be because of ‘sabotage of traditional values’ and it’s an entirely different story.

Spot the difference

Let’s take a look at an example: a YA fiction about boys slowly falling in love with each other, despite the age gap, legal norms and social disapproval. It has a historical setting and touches on class privilege, so was banned — but not in Florida or any other conservative part of the US. For the same reasons as ‘violating traditional values’ and ‘corrupting children’s minds’, Summer in a Pioneer Tie by Ukrainian-Russian duo Katerina Silvanova and Elena Malisova was banned in Putin’s Russia.

The Russian anti-LGBTQ ‘propaganda law’ was caused by condemnatory parliament discussions, and followed by a massive series of book bans, including Summer in a Pioneer Tie. New legislation prohibited all non-heteronormative representation in any Russian media, including literature.

Russia, as well as the US connectives, operates the rhetoric of saving a society from the threat of… well, perhaps, they mean democracy and the ability to explore your identity. But they prefer traditional values, stability, and ethical dignity. That is how you create imaginary enemies or “others” (check out Zimmel’s ideas on that!). Until you have an enemy to fight, you’re safe to rule. Seems like a classic dystopian plot.

Rebel. Reread. Repeat

The situation is quite disturbing. But what can be done about it? Let’s go back to Penguin Random House‘s award idea. They offered a $10,000 (£8,168) prize to a high-school student planning to attend university in 2024 and created an essay about how a banned book changed their life. With that award, they’ve done several things:

- Raise awareness about the problem. Yes, it is still a thing and an important one. The first step to approach any problem is to know about it.

- Drew attention of high-schoolers. The cash prize is something worthy to talk about. In our society, it adds value to the story, even if we don’t like it. And high schoolers as the target (and targeted) audience can finally be active agents of discussion.

- Most importantly, they shared real stories. The whole campaign is in fact about how so-called ‘detrimental books’ changed real lives. Some were about stories told by young readers, not some ethical abstractions. The ones who instrumentalise ‘traditional values’ for maintaining control and power obviously won’t be touched by teenage insights. But it may influence other young people and even parents to reconsider the value of banned books.

Penguin Random House is firstly a corporation, which has sources to launch an award and raise a discussion. But it’s not a matter of sources only. Everyone can make their contribution, with or without awards. Everyone can share their stories about the power of books to change lives, views, and maybe make a change themselves.