The intricacies of Saltburn: Elordi and Keoghan in a harrowing power play

By maariyadaud

Emerald Fennell’s latest film, Saltburn, presented to us a reimagined 2006, with Jacob Elordi as its most glittering star. Set within the confines of a sprawling country house, Saltburn’s dazzling yet disturbing plot was one nobody missed. It’s a modern gothic, a fever dream of excess and hedonism employing all our senses. The film emulates a feeling of stepping into a Caravaggio or Gainsborough painting from its soft lighting from one end, deep shadows and a composition that feels like a haunting portrait of power. What is so alluring is how familiar it seems, and yet, that’s what makes it so uncanny. Saltburn takes rich British tradition and turns it into a subject of debauchery.

This article contains spoilers.

Saltburn‘s tone and style make it feel jarring and confusing. The Midsummer Night’s Dream party feels like déjà vu, a sort of narrative within a dream, with people you know emerging as creatures – hooves and antlers and all. Whether the plot twist was a shock or not, what is a shock is the way the characters react to it. It’s realising Oliver (Barry Keoghan) is not who you thought he was. It’s the family acting like everything is okay when their own son has just been killed. It’s Farleigh (Archie Madekwe) and Venetia (Alison Oliver) being completely out of their minds. Venetia is fascinating; a beautifully tragic girl, who lies languidly above a pond, dying in the bath with her entire body submerged and her hair splayed. An awful rendition of Ophelia.

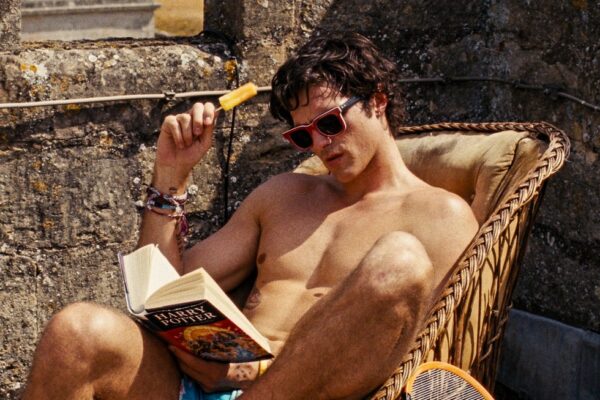

The warring sides to Oliver’s character are discomforting in themselves. He is awkward, clumsy, and shy in comparison to the tactical, cunning, and confident boy he becomes or has always been underneath his façade. Saltburn begins with Oliver’s monologue of his love for Felix (Jacob Elordi), quickly we realise he is the main character, an all-encompassing and dominant individual. Our focus is on Felix, but Oliver is the one who guides this focus. It’s hard not to adore Felix, and it’s obvious that those around him are just as mesmerised as audiences are to him. It seems everyone is clamouring for his attention whilst he is blissfully unaware of his power. He is a king in his own world.

Is Saltburn a shameless glorification of the struggling working class, or so much more?

Saltburn unravels the story of Oxford student Oliver Quick, unable to fit in at university he befriends a boy called Felix Catton. In an unexpected turn of events, Oliver is invited to his home for the summer, following the death of his father.

The film received a mixed reception. Some said it was sparse in terms of character development, others agreed that it should have been turned into a TV show to allow more of this development, and to enhance its richness and depth. I honestly did not see this at all I think it was artfully crafted. I am no stranger to this genre; the satire of the rich or elite through their glorification. Each still was perfect, beautiful and sickly. Fennell, says, should be able to pause the movie at any moment and see vast amounts of detail contributing to the film’s overall meaning.

More and more, Saltburn feels like a power play between the upper and middle classes. In Britain, we live in a society where classes are less about household income or your parents’ jobs (such as in America) and are more focused on your surname and heritage. If you’re part of the upper class, most likely your surname is from old money, and no matter how much the middle strives to be part of the upper, even if you are earning hundreds of thousands, you cannot simply be accepted. This is what makes the movie so unsettling. It takes this British tradition and twists it, to give us a story of a boy from sufficient money (Oliver) who wants so much more than just that.

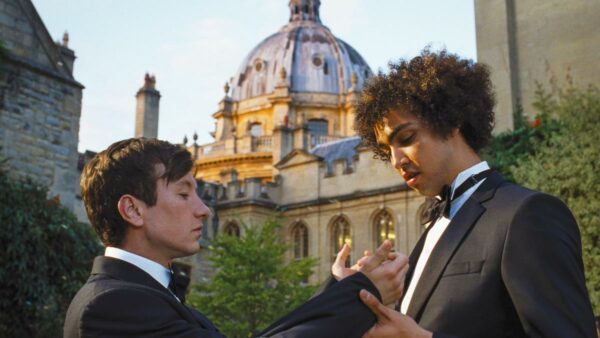

Oliver is fighting desperately to be part of a class of people that shun him with their very identity, and he doesn’t realise that he literally cannot be a part of it. The surname ‘Quick’ holds no gravitas; the surname ‘Catton’ demands attention. Farleigh does not let Oliver forget this. Down to the sleeves of his tuxedo, Oliver stands out like a sore thumb amongst the upper class. Farleigh, with his trained eye and upbringing within the Cattons, immediately recognises the suit as a rental, which didn’t even occur to Oliver.

There is also that one moment at breakfast when Oliver deems the meal as a “full English” whereas the actual term would be a “cooked breakfast”. The subtle language differences make the hierarchy so obvious. Oliver then has an awkward struggle with Duncan (Paul Rhys) as he complains about runny eggs, though one would think that he would know what a cooked breakfast entails. I believe he is having a power play with Duncan here.

This all leads us to feel sympathy for him. In the beginning, one cannot help but side with bumbling Oliver, who struggles to find his feet and fit in. We continue to side with him as Farleigh patronises him. We side with him when Duncan seems unnecessarily cold. But that is because we don’t know any better. We are stuck within the classic loop of literature and film, that rich equals bad because they are privileged, and poor equals good because they struggle.

In this film, everything is thrown on its head. The Cattons, particularly Felix, are unbelievably gracious to Oliver, despite their underlying problems, and Oliver repays them with nothing short of cruelty. Therefore, when Duncan appears from nowhere and catches Oliver when he is alone, it feels very strange that the man should target someone who is nothing more than an awkward boy trying to find his way around a castle he is not used to.

It’s ironic that “Everyone gets lost in Saltburn”, was uttered to Oliver as it would seem applicable to everyone except him. Even Pamela (Carey Mulligan) doesn’t know the way to the kitchen. Yet Oliver never gets lost. He seems to be the only outsider who knows his way around, and knows exactly what he is doing. This makes him unbelievably powerful. Everything for him is planned out.

With inspiration from major films and literature such as Brideshead Revisited, Rebecca, and The Talented Mr. Ripley, Saltburn can be compared to a vampire film. The infamous period blood and bathtub scenes are exactly what makes this. Oliver, as the vampire, rules the estate and physically consumes the ones within it by night. By indulging in the literal bodily fluids of the inhabitants, it is made obvious that owning Saltburn isn’t enough for him – he must literally embody and ingest them. The heart-swelling, soaring music in the background feels like witnessing history be born, the singers serenading the name of Oliver. He is glorified. He is powerful. He is an enigma.

What is so incredible about Saltburn is how everything is meticulously and purposefully thought through. The fashion choices from the polo shirts down to the eyebrow piercings all bring 2006 to life. However, we see a direct difference between the style of the students and the style of the Cattons, which is just one example of their connections as a rich family. They clearly wear clothes custom-made for them.

A clever stylistic choice is the feeling like we’re within a Renaissance painting, only to look closer and see how modern it is. In the karaoke scene, the guests are laid out as if they are ready for a portrait to be painted of them, yet the subdued and harrowing lighting comes from a crappy TV in the corner. One scene zeroes in on Felix making out with a girl, towering mountains soaring behind them like piles of gold and decadent jewellery. They glint in the low light. When you look closer, you realise it is the sharp edges of crisp packets and cans of Coke that catch the light. The movie has the feeling of luxury, decadence, and allure, yet could not be any more rubbish. It perfectly encapsulates the innocence and mess that comes with being a teenager, enhancing its authenticity while still building a narrative of wealth and class.

Fennell blurs the lines between upper and middle classes, between family and friends, through powerful dialogue, music, and characters that feel like people you have already met in a dream. Felix is a king, dying with his wings intact, and his family remains watching their sabotage posthumously as puppets on the grand stage of Saltburn.