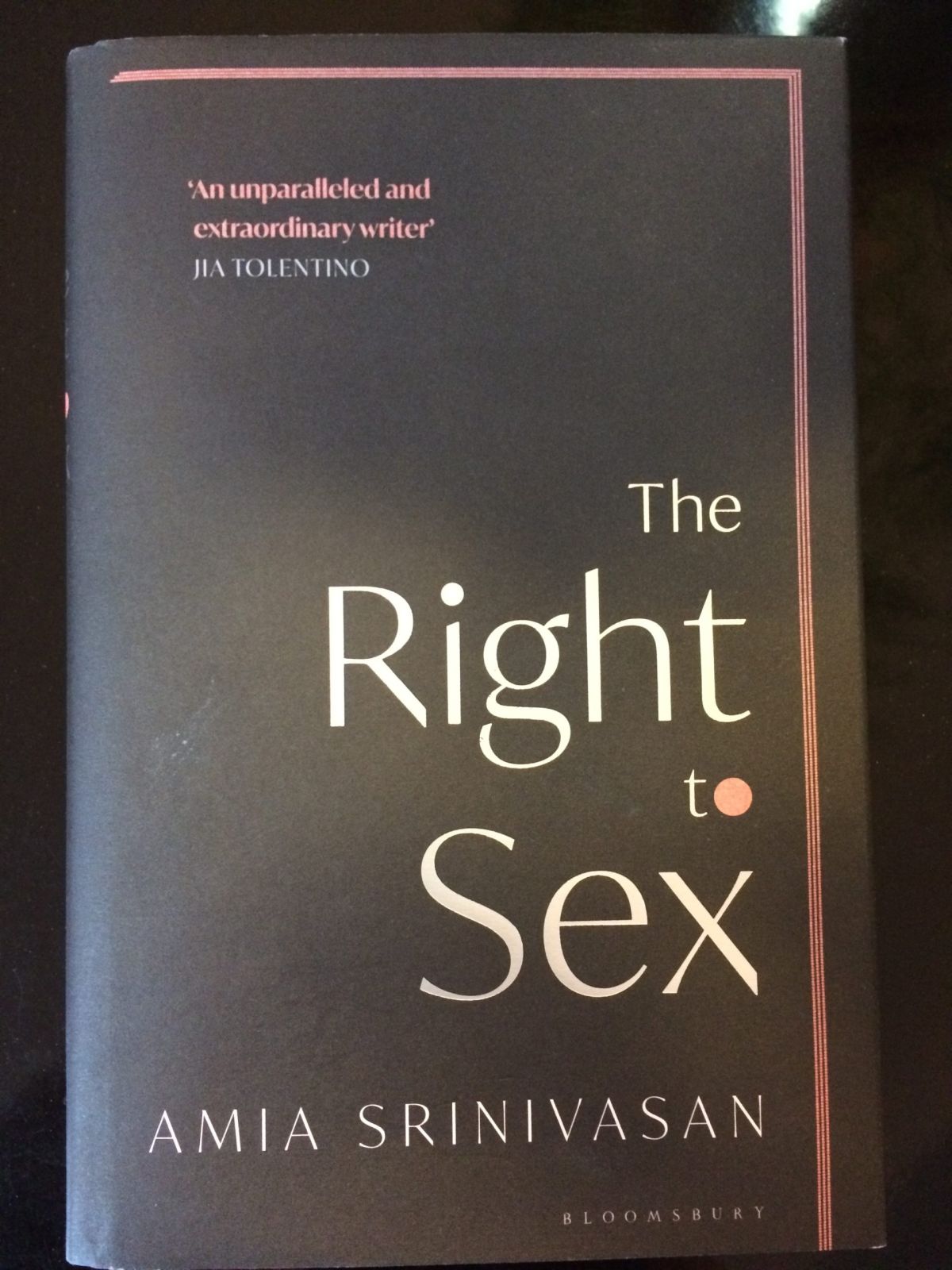

Amia Srinivasan’s new collection of essays, The Right to Sex, address, with deep thought and precision, the current state of sex. Covering topics ranging from incels to porn to MeToo, Srinivasan draws on a diverse breadth of feminist theory. Almost effortlessly, she pieces together various and differing viewpoints, asking her readers to look at hot, topical debates rigorously. She encourages readers to consider slowly and carefully how we might begin to understand how people have, think, and talk about sex.

Srinivasan is a philosopher, and is currently the Chichele Professor of Social and Political Theory at the University of Oxford. The essay from The Right to Sex that I will focus on, Talking to My Students About Porn, is drawn from her conversations with students, demonstrating how her work originates from a keen desire to engage with and learn from other people.

By no means dictating a singular viewpoint to her reader, Srinivasan strives to coax us into conversation. Her writing style is so clear and precise that it almost makes the reader forget that each sentence is packed with information, research, and provocative and ground-breaking ideas. Her work comes close to genius, but she has none of the pretension of one.

“At a practical and technological level, albeit not a philosophical one, the internet has settled the ‘porn question’ for us. It was one thing to entertain the possibility of abolishing porn when porn […] was, in principle, containable. But in the era of ubiquitous, instantaneously available porn, it is another thing altogether”

Talking to My Students About Porn begins with a succinct and riveting account of the so-called ‘porn wars’ that divided the feminist movements of the 1970s. Srinivasan describes the divide between pro-porn and anti-porn feminists. The former viewed porn as a potential vehicle for the expression of sexual freedom, whilst the latter saw all porn as an ideological tool of the patriarchy: “porn is the theory, rape is the practice”. Srinivasan draws on notorious anti-porn feminists such as Catherine MacKinnon to ask questions about the very different reality of porn today.

She describes how, surprising her expectations, her students were riveted by anti-porn theory. She found that it chimed with both her male and female students’ sexual experiences. They described how men come to sex with a prescribed idea of how to perform, many of them having accessed porn from an incredibly young age.

Srinivasan highlights how sex education is limited in its ability to combat the ubiquity of porn. Particularly since educators are unable to treat the porn as a text that they can assign to a class and then critically deconstruct as this would be illegal.

Srinivasan shows how anti-porn feminist theory can often align with the patriarchal state, describing how MacKinnon was involved in drafting certain state legislature in the US. This alignment with often reactionary and carceral modes of government demonstrates the danger of a vehement anti-porn stance. Srinivasan describes some UK laws regulating the creation of porn. For instance, making difficult the filming of lesbian, BDSM, and femdom porn, effectively making only ‘vanilla’ heterosexual, penetrative sex legal and easy to film.

“Whatever authority porn has is granted by those who watch it: by the boys and men who trust porn to tell them ‘what’s doing’”

Her discussion of feminist and queer porn is interesting. It becomes a potential alternative to mainstream porn, with Srinivasan suggesting that it could even be subsidised by the state in order to access wider audiences and remove paywalls.

Srinivasan’s essay, and The Right To Sex as a collection, demands that the reader take responsibility for what she is discussing. Srinivasan’s work does not provide us with conclusive answers, but gives us the tools to piece together our own approach to sex, our own approach to the way we treat those we love, and especially those we do not.