Hylas and the Nymphs: more than meets the eye

Manchester Art Gallery deliberately provoked discussion last week, by removing the painting Hylas and the Nymphs from their website and walls, leaving a blank space for audience debate.

The painting by Victorian Romantic John William Waterhouse was targeted for its enticing antagonists: seven naked nymphs who are seducing Hylas with their topless — yet adolescent — beauty.

The public gallery claims to have been conducting an experiment by challenging the male gaze in Victorian fantasy and the modern-day attitude towards the female nude, in light of the #metoo campaign and recent sexual harassment revelations which have shaken the culture industry and the world of politics. The painting was down for a total of seven days — one for every nymph — before it was re-hung thanks to public demand.

The youthful appearance of the mythological females depicted was the main point of contention. The general consensus so far, however, seems to be that the painting wasn’t offending anyone. In most cases, a greater contempt has been expressed towards the removal itself, branded as conservative censorship by many.

As a matter of opinion, I quite like the painting. I have seen Hylas and the Nymphs numerous times and it has never stood out to me as being offensive.

I don’t believe that it is remarkable enough to be controversial, and I don’t believe therefore that this painting would influence an audience to think differently about sexual entitlement.

What did offend me about the event is Manchester Art Gallery’s disingenuous and opportunistic co-option of a pressing social and political issue, exploited to ignite a media stunt. It saddens me to criticise one of my favourite UK galleries, but there are numerous reasons why we shouldn’t buy into this public performance.

Firstly, the project was announced “in anticipation” of the gallery’s upcoming Sonia Boyce exhibition. Manchester Art Gallery has harnessed this debate as a tool to promote the artist’s work, a fact that they have been relatively transparent about.

It is also not unreasonable to imagine how the re-opening of the Whitworth Art Galley has cast a shadow over Manchester’s trusty city gallery throughout the past three years. Without any sort of permanent collection, the Whitworth’s flexible blank-canvas layout has been able to attract increasingly impressive names such as Andy Warhol and Steve McQueen, leaving the lesser-known names and more localised narratives to its public companion.

Manchester Art Gallery’s intended display of integrity in this instance, purporting an interest in contemporary public opinions, is clearly an attempt to update itself, by engaging with current cultural affairs.

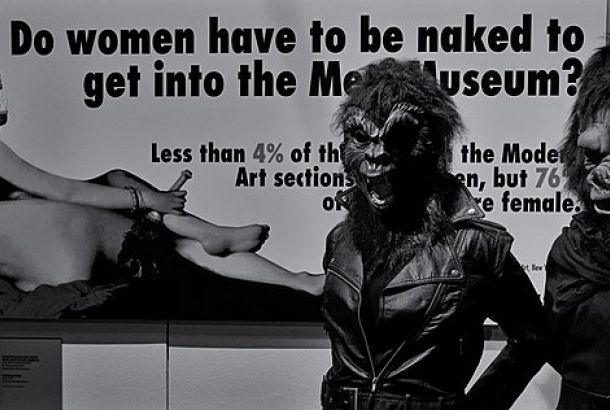

A similar event took place in the press a few months ago. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York declined to remove Therese Dreaming by Balthus from public view, despite a large petition demanding that it be taken down. The curator of the Hylas’ media circus, Clare Gannaway, likely took inspiration from the Met’s negative press, which was publicity nonetheless.

It’s not hard to sympathise with the Met’s critics, who argue that Balthus’ depiction Therese, as a highly sexualised young girl, actively promotes paedophilia.

When considered within these wider walls, the connection between Hylas and #metoo seems a little more contrived.

I would also argue that the Manchester Art Gallery never intended to permanently remove a key piece of their collection, if this had been the persuasion of the public’s verdict.

You might be interested to visit the gallery (now that they’ve swiftly re-hung Hylas) to view some of the other larger treasures they have on display. Less than a thirty-second walk from Hylas you can see Sappho, the ancient female poet, portrayed by Charles-August Mengin as stormy embodiment of busty sexual energy.

Or, you could see The Sirens and Ulysses by William Etty, a painter who’s academic obsession with the female form has long been called into question.

If you look closely at this painting, which takes up nearly an entire wall, you can see that Etty spent a vast amount of time painting the naked women. So long in fact that he ran out of time to finish the ropey background, that poorly contextualises their generous nudity within a loose mythological theme.

I don’t believe that any of these artworks should be taken down, but it seems that Manchester Art Gallery doesn’t think so either. There is a definite irony in this marketing campaign’s success. The attention Waterhouse’s painting has attracted has led to its image being circulated more than ever before. It has developed a fresh infamy.

Hylas and the Nymphs is nothing but a throw-away manifestation of an outdated Victorian imagination, a specific form of misogyny which has been regarded as problematic ever since it began. Whether or not we do continue to revise the art on display in our public collections is to be seen. This tired debate has resurfaced in the Western art world time and time again.

As a matter of urgency however, I think it should be asked “is it really fair to equate a Victorian mythological fantasy, with the living instances of sexual assault and abuse that we face today?”