Time testing The Bechdel Test

By pipcarew and Daniel Collins

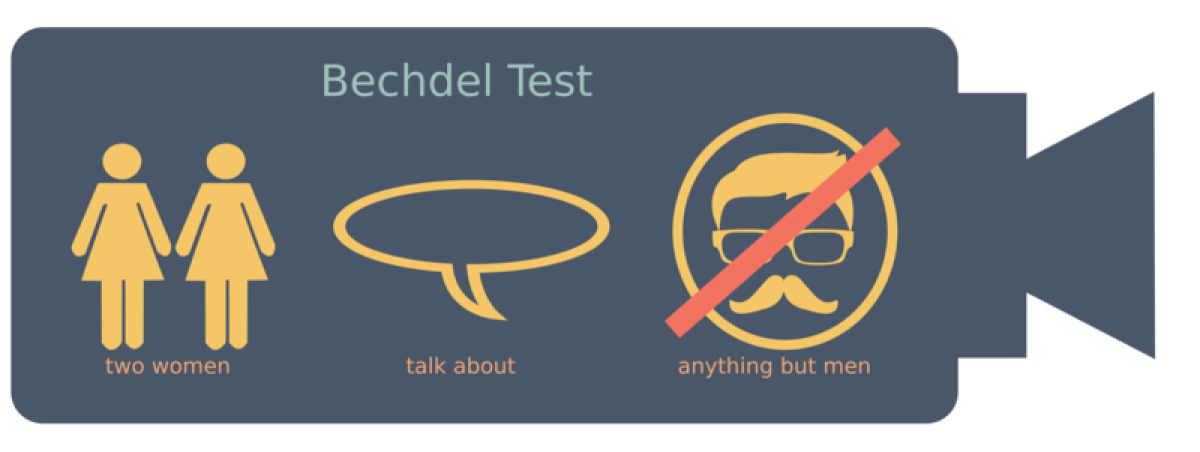

Since film began there have been two indicators of agency on-screen: speaking and looking. Until very recently who gets to speak and look has been disproportionately distributed. For many years, female characters have been the receptors of looking but have been silenced in the script. Alison Bechdel’s 1985 comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For offered a solution to gauging female agency in film. The rules of The Bechdel Test are simple: in order to pass, a film must feature a conversation between two named female characters which does not revolve around men. It’s a deceptively easy-sounding threshold and yet many fall short.

The test was adopted by feminist groups in the late 1980s as a means of inciting Hollywood screenwriters into creating female characters whose lives could be independent of men and romance. It is inarguably a useful tool to gesture towards what audiences require for convincing three-dimensional characters and combats that tired stereotype that women speak more than men. The Bechdel Test is not, however, a guarantor of the quality or authenticity in the depiction of a character, it is simply an interesting tick box for film watchers to contend with. If the test is taken as gospel then Twilight (which passes) deserves a place in pop culture whereas The Godfather (which doesn’t) should be consigned to the annals of history and written off as drivel. The absoluteness of the test is certainly appealing, making it easier for audiences to choose which films they’d like to watch by eliminating the films whose writers have chosen not to make female agency a focal point. The test’s beauty is in its simplicity but this is also the foundation of its problems- its lack of nuance. Judging media based solely on a singular test will never be entirely satisfying when catering to spectator expectations. Can a film be considered feminist if it does not pass? We’ve selected three case studies to probe the sturdiness of the test in modern film: a rom-com, a western and a superhero film.

Blockbusting Old Stereotypes

When Birds of Prey erupted onto our screens in 2020 helmed by a powerhouse of women to rival the fictional Birds of Prey team (director Cathy Yan, writer Christina Hodson and producer/star Margot Robbie), there was much discussion about the difference between how Harley Quinn was portrayed in the original Suicide Squad versus her new solo outing. In Birds of Prey, Quinn’s outfits are still extravagant and glamorous but the gaze of the camera is no longer voyeuristic. For example, Quinn’s iconic booty shorts are shown from a respectful angle and not as an introduction to the character. The distinction between both iterations of the franchise being who the film was made by and the audience that was kept in mind. Diverse creative power behind the scenes makes a noticeable difference to how convincing representations are.

Moreover, it doesn’t shy away from rom-com plot elements as superhero films often do – the inciting incident of the film happens because of Harley’s breakup. Making the joker an absent figure as a prop used for subtext was a wise decision. Instead of the toxic relationship between Quinn and the Joker becoming the focal point, Birds of Prey is concerned with the mission to reclaim a sense of independence after a painful breakup. The scene that earns it its bechdel gold star is a conversation about battle strategy that the team have. Later on they also discuss relationships but as multi-faceted characters whose life and romantic goals are not mutually exclusive. Birds of Prey is an excellent movie with a predominantly female cast and creative team that just happens to pass the Bechdel Test.

Tall Girl: a Pass and a Fail

Nevertheless, a film can pass not only the bechdel test but also be directed by a woman and feature many women in key areas of its production and still contain some potentially harmful ideas about women’s role in society. One example of this would be Netflix’s Tall Girl film series, the latest of which (Tall Girl 2) has just recently dropped on the platform. The films follows 6 ft 1 girl Jodi who struggles with her place within an American high school due to her height and problems only get worse when she begins to enter the dating realm. Whilst the idea that being tall is a problem to make a whole film about is entirely silly in its concept, that’s not what we’re here to discuss. However, the melodramatic tone of this dramatic conceit is reflected elsewhere in the film as it appears to somewhat knowingly lean into its rather stereotypical story that really feels like an adapted LifeTime or Movies24 script. This is not bad in and of itself, such films are made because their formula is comforting, their drama may be mechanical but is often successful in its emotional manipulation and their characters may be thinly drawn but their problems never feel too real as to take you out of the simplistic escapism. However, when the aggressively heterosexual and vaguely sexist politics come to the forefront, the illusion can become somewhat damaged.

This is very true of both Tall Girl films, particularly the 2022 sequel. As a teen romance, of course the happy ending of both these films is a coupling between Jodi and her desired partner. This is not necessarily a bad thing but as Jodi essentially goes through each film becoming more and more comfortable within herself and exploring her own talents and fears, the idea that all of this boils down to getting the right man is a little disheartening. The sequel doubles down on this problem by not only repeating the same narrative arc for Jodi but also by providing her previously independent and creative friend Fareeda with a man of her own. Whilst their chemistry is okay and it does give a proper arc for her character that exists outside of Jodi, it does give off the idea that no woman can truly be independent.

However, the films’ most off-putting aspect is its overwhelming emphasis on heterosexual marriage. During the sequel, Jodi performs in a school production of the musical Bye Bye Birdie. One of the few musical numbers that is highlighted includes the chorus: “one boy, that’s the way it should be”. Going on to later say that this should be “forever and ever”. The specific highlighting of this musical number comes off as a strange proclamation that heterosexual unionship is the one true divine goal of life. An idea that is only further emphasised by the aforementioned pairing off of the main characters. This comes in the same film where the idea of someone being queer seems to be a distant one and the main female characters’ passions are singing, modelling and fashion. It all just seems a bit limiting. Even if the film is not necessarily doing anything overtly wrong, by eschewing other perspectives and fitting all too neatly in the roles designated by the patriarchal structure, it comes off as false and weirdly preachy. No matter how easy it may be to watch or as harmless as it feels, it ultimately does little other than reinforce existing structures, even with a narrative that is told by women and about women.

The Power of the Patriarchy

Jane Campion’s 2021 film The Power of the Dog is currently receiving much well-earned Oscar buzz. This western is also an illuminating example of where the Bechdel test falls short in assigning criteria for feminist film. Kirsten Dunst’s character, Rose, marries ranch owner George Burbank, Jesse Plemons. According to the time period, this marriage removes her from her occupation to live on George’s ranch, which is a distinctly masculine environment. She endures psychological bullying and manipulation from George’s enigmatic brother, Phil, who contends with repressive forces in the rejection and concealment of his own sexuality. In The Power of the Dog gender is a weapon and femininity is a threat. Each character that exhibits typically feminine characteristics is punished and belittled by Phil, particularly Rose’s son, Peter. Therefore, it is the desire to erase femininity from the hyper-masculine setting of the ranch that is a stronger commentary on gender imbalance than any overt conversation between women may have been.

In one scene, Rose enters the space where the cook and maid are discussing, telling them not to stop on her account. In this instance, the lack of dialogue between women indicates the divisions of the domestic space. Rose’s inclusion in the conversation would have been anachronistic; she is separated from them due to her class and connection to the ranch owner both independent of her control. As director and screenwriter, Jane Campion uses this omission to confront female isolation in a specific era. Although it doesn’t pass The Bechdel Test, the Power of the Dog should be considered a feminist film as it explores the restrictions of gender in those huge isolated spaces where politics is not immediately apparent. Campion’s film confirms Allison Bechdel’s statement that ‘you can certainly have a feminist movie where there’s only one woman – or no women.’

Cherrypicking: The Bechdel Test Updated

Despite its rather binary rules, the Bechdel Test has not stayed stagnant within popular culture. In fact, it has inspired many other similar tests such as those that consider BAME representation and the Vito Russo Test, which attempts to track LGBTQ+ representation in the cinema. Nevertheless, these other tests reject such simple criteria and begin asking more complex questions surrounding narrative function and character’s identities. Whilst it is certainly a positive idea to interrogate the representation and how it functions rather than simply stopping at the first step, such tests lack the simplicity and therefore the raw data that is so key to the Bechdel Test. One alternative that has been proposed is the wonderfully named Sexy Lamp Test, which asks the very simple yet infinitely complex question: could you replace your female character with a sexy lamp and would the plot still work?

Although this particular test may sound ridiculous, the problem of representation is still very much a real one. The conversation must keep evolving and not stop with the Bechdel Test. However, this also does not mean to have to abandon it altogether. Review aggregator website Cherry Picks is a shining example of this. Built as a sort of competitor to Rotten Tomatoes, it only considers reviews from female-identifying and non-binary critics. Moreover, for each film reviewed (which includes the majority of new releases), there is another metric known as the Cherry Tick. This tracks if a film: a) Passes The Bechdel Test, b) has women in key areas of production, and c) is written and/or directed by a woman. A film gets the tick if it passes any one of these three criteria. Although it inherits many failure’s of the Bechdel Test in the sense that not every representation is necessarily good, it does address the very real gender disparity that occurs behind the scenes in production.

Where are we now?

As the investigation furthers, the burning question seems to be: can there ever really be a good test for media representation that captures nuanced depictions? Additionally, will a film ever be able to tackle every issue plaguing society in a satisfyingly in-depth way? The answer in both cases seems to be no; there is no prescriptive checklist as to what will make a film entertaining and its depictions arrestingly unproblematic. It’s very much a matter of personal taste. Each case study examined here is not an isolated one but rather emblematic of certain trends where the industry has had success or falls short.

So, instead of being a blanket measure for whether a film/tv show is worth your time, the Bechdel Test is best used as a tool to test whether the film will speak to a larger human experience. It was only ever intended as a conversation-starter rather than the end point to all discussions. It is no longer enough to placate the public with mere representation. As we look ahead to what’s next, maybe let’s look beyond the test and embrace and interrogate the ambiguities that make film so worthwhile.