Creating a play that is both dystopian and intimate is no easy feat – but writer Sam Steiner and director Josie Rourke have succeeded in doing so. I can imagine the play working better in a smaller, more intimate space – the way it began at the Edinburgh Fringe – than a theatre as big as Manchester Opera House, but the stage design (Robert Jones) captures the intimacy of the text.

Lemons Lemons Lemons Lemons Lemons (let’s just call it Lemons) is set in a dystopian near-future, before and after the introduction of a “hush law”, limiting citizens to a mere 140 words a day. Why? Who knows? That’s not really the point of the play.

The play, a two-person show, stars Jenna Coleman (Doctor Who, Victoria) and Aidan Turner (The Hobbit, Poldark) as a young couple coming to terms with the law. Bernadette (Coleman) is a high-flying lawyer from a working-class background whilst Oliver (Turner) is a freelance musician from an aristocratic background (he grew up in a castle) – and this occupational imbalance is a problem in their relationship.

The play tackles a great deal of issues throughout a mere 90 minutes, including class politics. Oliver is an anti-establishment, left-wing activist who claims to care deeply about the working-class yet seems to surround himself with fellow toffs and repeatedly talks over and for his own working-class girlfriend. He often reminds her that she is working-class, telling her that she should care about the hush law because of her background, but there appears to be an implication that he knows better because of his background.

This appears to be a criticism of middle-class lefties telling working-class folk what they need, and who to vote for, without actually bothering to listen to working-class people and their concerns.

Bernadette is not exactly indifferent to the hush bill but, rather, fails to take it seriously, by virtue of not thinking it will pass. This is surely a nod to Brexit, with scores of people not voting because they did not think a Leave win was possible – and perhaps even Trump’s win in 2016. Further, Bernadette does not initially view the bill with the same fear and fury as Oliver, who characterises it as fascist and a suppression of free speech.

This allows for a little philosophical debate. Is a limit on your words a limit on free speech? You’re allowed to say whatever you want – but only in so many words. Oliver argues that 140 words is not enough and that the law will unfairly affect working-class people and offers some loose explanations as to why. Bernadette disagrees, for the law will apply to everybody, but she appears a little sheltered to class politics and working-class issues, perhaps because she is an (all-too-rare) example of social mobility and meritocracy.

Things get a little heated when Oliver sarcastically remarks, “It’s not fracking,” which Bernadette finds patronising. An argument ensues, with Bernadette eventually (and condescendingly) snapping, “I’m a lawyer,” to gasps and laughs from the audience. Hypocrisy at its finest, recognisable in all humans; we often hold others to higher standards than ourselves.

I was quite humoured by the lawyer remark for I’m very much that person. “I’ve got a first-class Politics degree from one of the world’s leading universities. Where did you graduate? The University of Life?” is something I’ve said in Twitter arguments. More than once.

The lawyer remark also captures Oliver’s silent but obvious embarrassment that his working-class girlfriend makes more money than he does. Oliver admits to hating Bernadette’s career but is too proud to admit to said embarrassment. Bernadette can read through the lines, though. “I’m sorry I make more money than you,” she later tells him, with a sense of understanding, a touch of sarcasm, and a sprinkling of pride.

The play is not linear. Rather, it repeatedly jumps back and forth, which can be a little disorienting and difficult to follow, but, for the most part, works wonderfully. Some scenes are directly correlated. At one point, the first line of one scene is similar to the last line of a previous scene; the scene changes are seamless.

The back-and-forth-ing offers a more complete look at the couple’s relationship, with things revealed out of sync, changing the way you had previously thought about a character, which would not have been the case if the play had been linear and we watched the characters develop before our eyes. I’m reminded of the recent Netflix series Kaleidoscope, which can be watched in any order. The order in which you watch it determines how you feel towards different characters – and when.

Further, a 90-minute, no-set, two-person show can be intense and tiresome, but the non-linear timeframe keeps you interested and intrigued.

We never meet any other characters. Even when the results for the bill are coming in, we do not hear the newsreader on the television; we just see Oliver and Bernadette react to it with shock and horror. The play is self-contained. Everything we learn about this dystopian world is through these two characters. The entire action seems to take place in the same location – though that is probably not the case, for the couple’s first meeting was likely not at the house they are living in now – which creates a feeling of claustrophobia and embodies the notion that “nothing else matters”.

Indeed, for all of Oliver’s concerns about democratic backsliding, the worst consequence of the hush law is what it has done to his relationship (or, rather, revealed about his relationship).

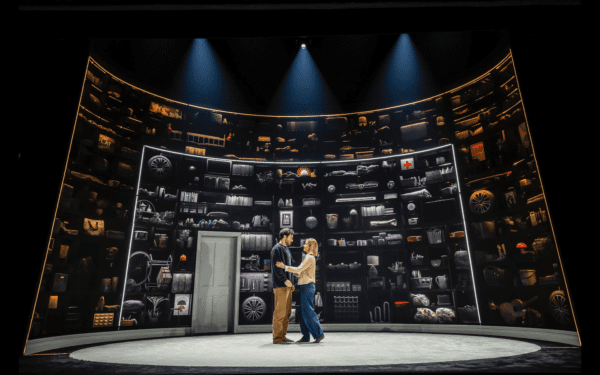

The claustrophobia of the play is enhanced by the stage design: the stage is bare, safe for a screen at the back of the stage, which encloses the action like a heavy hug. The screen is filled with images of stuff and more stuff; the only thing I remember is two digital clocks, which are turned on as the first post-hush law day approaches. It feels more domestic than dystopian – capturing the very essence of the play.

Towards the end of the play, the images on the screen move up, leaving solid black in its place. The abyss. Later, several domestic images appear on the otherwise blank black screen. It is a visual representation of the action of the play. A domestic dystopia.

Indeed, the play is not so much about the bill but, rather, how one (or two) reacts to the bill. The law is far-fetched and requires a suspension of belief but one can compare it to other controversial laws, referendums, etc. from the 2016 United Kingdom European Union membership referendum to the 2017 Turkish constitutional referendum. Politics can divide families because politics speaks to morals and values. Bernadette and Oliver align politically but they have different thought processes – and it’s pretty hard to explain your thoughts in 140 words.

Thus, the play is largely about communication – and a lack of communication. For example, a big reveal at the end of the play (a twist, of sorts, for it contradicts what we were previously told), and the other person’s near-indifferent response to that betrayal, reveals that something does not necessarily have to be said for it to be known. “I think I always knew,” says the betrayed.

Words are just words.

Lemons Lemons Lemons Lemons Lemons runs at Manchester Opera House until March 25. Whilst all available seats sold out ahead of the play’s arrival, ATG have just released some extra seats for each performance – due to phenomenal demand. The play ends its mini UK tour at Theatre Royal Brighton, where it runs from March 28 to April 1.