When Sheffield Theatres announced that they were reviving Miss Saigon, I had two questions: why, and why now?

Pretty much all 20th-century musicals about East Asians are racially problematic but Miss Saigon is in another league. Modern productions no longer employ “yellow face” (previously, White actors “blacked up” and wore eye prosthetics) but the story, itself, offers much to criticise.

Sheffield Theatres’ decision to revive the musical has unsurprisingly faced considerable backlash – but what the criticism is missing is that almost the entire creative team (including the Associate Artistic Director of Sheffield Theatres and co-director of the production) is East Asian. This is not just another White European fantasy but rather an East Asian reclamation. Asians are rewriting the narrative.

Read ahead for a considered analysis of the revival. Spoilers ahead!

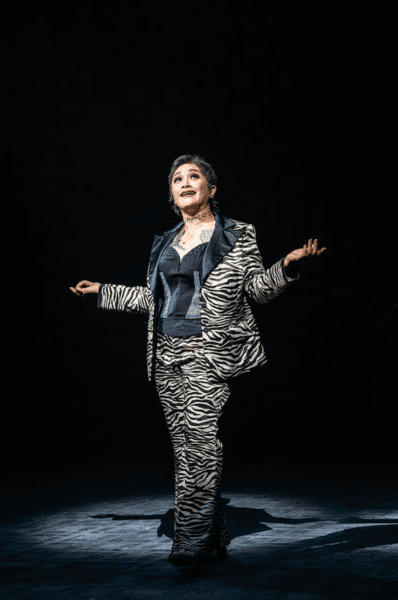

From the very beginning, it was clear that Sheffield Theatres were mixing things up because they announced that, for the first time ever, a woman (Joanna Ampil) would be playing The Engineer.

Ampil played the lead role of Kim in Miss Saigon on the West End, in the original Australian cast, and in the original UK and Ireland tour. She recently starred in Chichester Festival Theatre’s revival of South Pacific, which similarly reimagined its Asian characters – especially her character, Bloody Mary. I reviewed South Pacific last year, and I have twice seen the recent revival of The King and I, which has made a real effort to de-orientalise the musical (to use Edward Said’s concept of “Orientalism”). These triumphant productions show that it is possible to correct the flaws of racially problematic musicals.

Based on Puccini’s opera Madama Butterfly, itself based on John Luther Long’s short story Madame Butterfly, Miss Saigon similarly tells the tragic tale of an Asian woman (Kim) abandoned by her American lover (Chris). The setting is relocated to Saigon during the Vietnam War.

Kim is a “bar girl”, or a prostitute, at Dreamland, which is ran by The Engineer. Brothels have been led by both men and women so casting a woman as The Engineer is not historically inaccurate. In this adaptation, This Engineer is, essentially, a Madam.

Whilst the original story reveals the troubles of The Engineer, especially as the mixed-race son of a prostitute, he is very much a baddie. By making The Engineer female, the context is changed entirely. She is struggling too, not only as the citizen of a war-torn country under totalitarian rule, but also as a woman. She exploits young women because she is desperate herself. In this version, she cares about her girls, especially Kim, but she has to prioritise her own survival – because if she won’t look out for herself, who will?

Her big number near the end of Act Two, ‘The American Dream’, is arguably the revival’s best. The Engineer longs to migrate to America, and she views Kim’s bastard child, whose father is American, as her ‘ticket’ out of Vietnam (Vietnamese con artists claimed to be related to Amerasian children to migrate to the USA).

The number sees her transform into Marilyn Monroe in ‘Diamond’s Are a Girl’s Best Friend’ in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, complete with a pink gown and gloves, silver jewellery, and a blonde wig. She becomes a beautiful blonde bombshell.

At the end of the number, the ensemble rip everything away from her, representing the futility of her dream to escape but perhaps also the futility of the American Dream itself. The Engineer has a naive, romantic view of America, especially as a woman of colour. Her vision of America is based on what she has seen in glitzy Hollywood films.

Whilst making The Engineer female removes a story of patriarchal power, that is explored with Thuy (Ethan Le Phong), a Vietnamese man betrothed to Kim when they were children. It is a shame that the only named adult male Vietnamese character in the musical is a chauvinistic, nationalistic brutalist but the musical needs a villain – and his fate sets into motion the second act.

The bigger issue I have is the musical’s portrayal of Americans compared to the Vietnamese. The musical does not engage with the reasons behind the war. The Americans are portrayed as flawed (and they are redeemed in ‘Bui Doi’) whilst the Vietnamese are portrayed as evil (especially in ‘The Morning of the Dragon’). The revival actually makes the Americans more sympathetic, portraying American soldiers as victims of exploitation themselves, whilst the Vietnamese soldiers are like robots, brainwashed by a totalitarian regime.

This musical ultimately aligns with the Americans, who senselessly entered a civil war that was none of their business – and ultimately lost. The Americans massacred Vietnamese civilians and used weapons such as Agent Orange, which is still causing birth defects – but the musical fails to acknowledge any of that. It doesn’t even tell us why the countries were at war. One wonders if the writers just thought Saigon during the Vietnam War would be a cool setting.

Sheffield Theatres do they best that they can to rewrite the narrative but these problems are so embedded into the story, script and songs that they cannot be properly interrogated without a complete rewrite, especially because this is a sung-through musical.

I hated ‘Bui Doi’ in the previous production I saw. In this context, “Bui Doi” refers to the mixed-race illegitimate children that American soldiers left behind, and this number offers a White saviour complex. It’s a real crowd-pleaser, in which White audiences celebrate White men for finally giving a flying toss about the half-breed bastard children they abandoned. Meanwhile, ‘You Will Not Touch Him’ suggests the Vietnamese wanted to exterminate Amerasian children, in another ridiculous juxtaposition of the Americans and the Vietnamese.

This revival makes some successful creative decisions and changes. For instance, in previous productions, ‘Bui Doi’ sees American veterans stand together, chests pumped out like superheroes, ready to rescue poor brown kids. The revival changes the context: the struggling soldiers seem to realise that they, themselves, are exploited victims of a futile war; they come to their senses and regret their crimes.

‘The Morning of the Dragon’, meanwhile, is no longer the oriental spectacle that it has been in previous productions – but without the spectacle (this non-replica production has a much simpler set), Miss Saigon is not quite as interesting as I remember. The spectacle is one of the musical’s biggest appeals – but also one of its biggest problems.

Essentially every number has been reimagined visually. The opening song, ‘The Heat is on in Saigon’, sees American soldiers visit Dreamland. In previous versions, scantily-clad Vietnamese prostitutes danced for the soldiers (and for the majority White audience). In this version, it is not the prostitutes that dance but the soldiers. The (White) male gaze is destabilised. Genius.

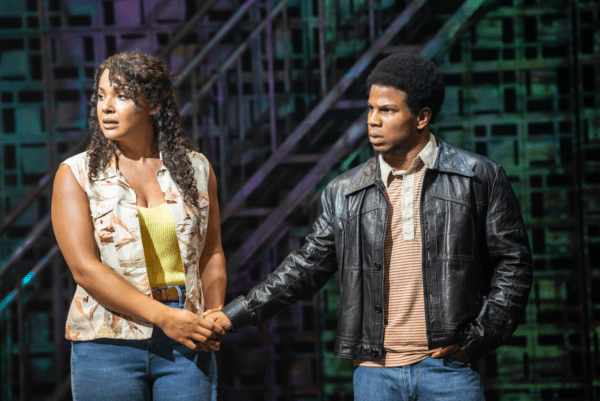

As talented as Christian Maynard is, I have mixed feelings about the decision to make Chris African-American, for it negates the White supremacy which I felt was important to this story of exploitation. I guess the creatives wanted to portray a story of true love, rather than just a White man having fun with an young Asian woman and then abandoning her for a hot blonde.

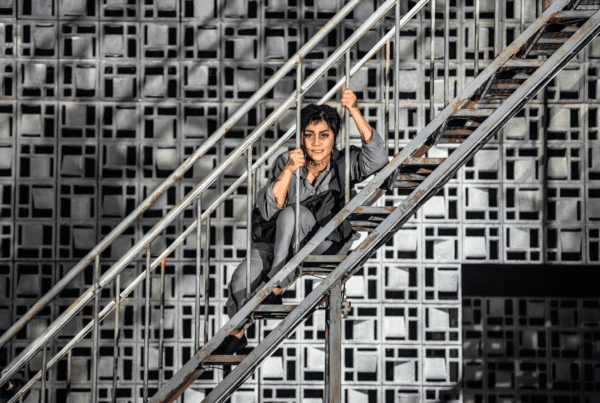

There is even a flashback to Chris leaving Saigon, in which he dangles on a helicopter’s rope ladder (incredible staging – bravo, Sheffield Theatres!). Kim runs to the top of the steps, and the pair reach out for each other, but they are too far apart. Chris truly loved her.

There is a real missed opportunity in not acknowledging Chris’ race and how African-Americans were/are exploited in the USA, especially in the context of the Vietnam War. Chris and Kim are both people of colour but the musical appears post-racial, at least with its portrayal of America.

Chris’ wife, Ellen (Shanay Holmes, the director and co-founder of Musical Con) is also African-American. She is a sympathetic character, especially because she is sympathetic towards Kim. She has an inner-conflict, and the audience are made to understand her moral dilemma.

Kim, meanwhile, is played by Jessica Lee (The Power, The Full Monty). Lee offers one of the most beautifully devastating performances I have seen onstage, especially with her roaring renditions of some of the musical’s most recognisable songs: ‘The Movie in My Mind’, which sees her naivety foiled against fellow prostitute Gigi’s rationality of their situation; ‘Last Night of the World’, a romantic duet with Chris; and ‘I’d Give My Life For You’, which she sings to her three-year-old son, Tam – which (spoiler) foreshadows her fate.

Gigi is portrayed by Aynrand Ferrer, who was 1st cover Kim in the latest UK and Ireland tour and Alternate Kim in the recent Austrian production. I recently saw her in the UK premiere of George Takei’s Allegiance, which is also Asian-led. Gigi is criminally underwritten but Ferrer makes the most of her limited stage time.

Whilst Gigi does not traditionally appear in the second act, the Sheffield creatives have given her character more importance. When John (Shane O’Riordan), the American soldier who abandoned her, sings ‘Bui Doi’, he has a brief vision of her, and she appears later in the second act; her legacy lives on.

Indeed, the musical succeeds in humanising its Asian characters. When (spoiler) Kim kills herself and Chris comes rushing in, she does not just lie there and sing with him, à la Romeo and Juliet. She stabs herself but never falls. Instead, she walks around Tam, who is being comforted by The Engineer (who, in previous productions, exits after ‘The American Dream’, indifferent to Kim’s suffering).

The message seems to be that Kim is charge of her own fate – and her legacy – which reflects the words she sings to Tam: “They think they decide your life. No, it will be me.”

Kim is a victim, yes, but also so much more. She sacrifices herself for her son – so that he can have a better life. She walks around, as if still alive, because her legacy lives on.

The production ends (spoiler) with a man in the modern era switching off the television he had turned on before the show began. He puts his hands to his head, aghast at what he has witnessed. This is not a “movie in my mind,” this was real life.

During the curtain call, it is the actors playing Vietnamese characters (Kim, The Engineer, Thuy, Gigi, and Tam) who stand upfront. The non-Asian main characters (Chris, Ellen and John) are positioned behind them, which tells us that this is an Asian story; it is not just Asian entertainment for Europeans.

Sheffield Theatre’s Miss Saigon might fall short of being the radical deconstruction some were perhaps naively hoping for (for that, you’ll have to see untitled f*ck m*ss s**gon play, which is hilariously being staged at the same time). However it is a roaring revival nonetheless. Issues are examined carefully and critically. Asian characters are given agency, autonomy and humanity. Gone is the oriental spectacle which reduces Vietnam to big-budget pornography for Western voyeurs.

This is not just a revival. It’s not even just a reimagining. It’s a reclamation.

Miss Saigon runs at Crucible until August 19.