The Circle: A Surprising Piece of Performance Art

If you have watched anything on Channel 4 recently, you’ll have a seen an advert for The Circle. Appealing to the British tradition of detaching people from the outside world for the public to watch daily, the Circle sees each contestant fighting to become the most popular for a cash prize.

The Circle is similar to Big Brother, even down to its host, Emma Willis, who presented Big Brother from 2013 until its much needed death in 2018. The Circle, however, has a uniquely modern twist; whilst living in the same building, none of the participants meet, instead communicating through a social media platform named ‘The Circle’.

This allows for the contestants to perform however they like, and however they believe they will be best received. Some, like the delightfully antiquated and eccentric Tim, play as themselves. Others catfish as completely different characters. For example, James takes on the role of single mother ‘Sammy’, inspired by his own mother. In an interesting parallel, Katie, a single mum, plays her son Jay.

However, most interestingly, is the way in which gender presents itself in the game. Last year, Alex Hobern, won through catfishing as ‘Kate’, using photos of his girlfriend Millie. Alex, who worked for UNILAD and is now, according to his LinkedIn, a ‘social media influencer’, catfishes as a woman because he knew that women were typically responded to better on the internet.

When asked, Alex seemed to emphasise that being likeable was more important than working out who is, or not, a catfish. But, as the first few episodes of the season has shown, there is a natural scepticism towards other people in the circle. Perceived authenticity, then, is a vital element of being popular.

It is no surprise that women are subject to some of the most scrutiny. This year saw four women within the circle, including the catfish ‘Sammy’. Each of these women are conventionally attractive, and each carefully construct their image on the Circle. Brooke, for example, considers in the first episode whether her profile picture shows too much of her body. She decides to crop it. Emmelle, a lesbian, decided to ‘play it straight’ on the show, deciding that being able to flirt with men would increase her popularity. The way in which women have to carefully construct their identities on the internet is reflected on the show.

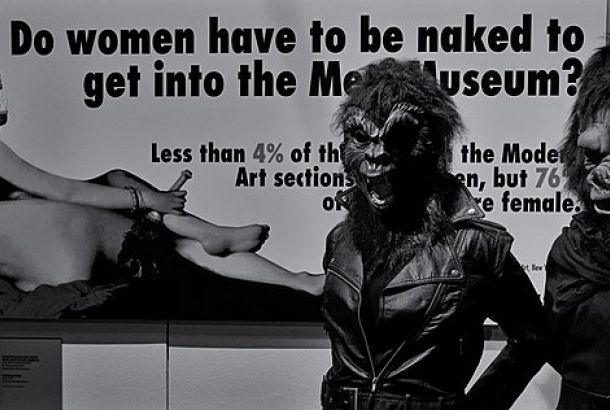

In recent years, feminist art has taken on the issue of female representation on the internet. Gender, in a post Judith Butler world, is considered to be performative, and women on the internet are expected, and socialised, to conform to established narratives. This was the subject of Amalia Ulman’s Excellences and Perfections, which saw the rise and fall of a fictionalised version of Amalia, as observed to the voyeuristic delight of her audience. Similarly, Ann Hirsch’s Scandalish Project (2008-09) proceeded the Instagram generation, but demonstrated the way in which we respond to women on the internet.

The Circle may have as little pertinence to the way in which we use and respond to the internet as Big Brother did to the surveillance state. However, watching the way in which people perform as their own gender or another? That is what’s keeping me watching.