The Godfather: Anatomy of a classic

By Joe McFadden

“I believe in America.”

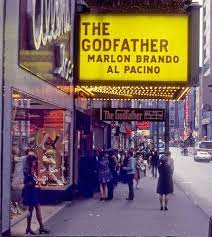

50 years ago one line introduced audiences to the saga that would come to redefine cinema: “I believe in America”. Cloaked in darkness, Bonasera’s monologue signposts what these films are ultimately about: family, fortune, capitalism, violence, and the corruption of man. The Godfather has since become a cultural juggernaut and a staple of modern cinema.

Released in 1972 as America grappled with Vietnam, Richard Nixon, and the end of the counterculture, The Godfather harkened back to an age where America was king, capitalism was thriving, and the mafia were in their golden age. It was this backdrop that set the stage for Coppola’s gangster epic to become an insurmountable success. As we celebrate the iconic trilogy’s 50th anniversary, it is important to remember what made the film a masterpiece in the first place and how, 50 years on, it still continues to mesmerise and entrance first time viewers.

The saga follows the story of the Corleone family, depicting their rise and fall throughout the 20th Century as America, much like the Corleone’s themselves, evolved from a promised land of dreams and wealth to a cesspit of corruption and decay. The first two films form a duology, showing us Michael Corleone’s (Al Pacino) transition from family-business outsider to ruthless mafia Don. The controversial third film acts as a coda, revealing the consequences of what happens when a man loses his soul.

America’s Underworld

It goes without saying that everything about The Godfather is iconic. Whether it be Marlon Brando’s infamous thick, mumbled accent or memorable quotes (“I’m going to make him an offer he can’t refuse”), the film has become such a huge part of American cinematic history that it is difficult to find something truly original to say about it.

From the opening scene it is clear that we are watching something truly special. The film opens with a close-up of undertaker Bonasera, his face shrouded in shadows and his eyes a vast gulf of darkness. Bonasera’s face haunts the film, introducing us to a world where morality has been replaced by sin. Credit for the camerawork goes to legendary cinematographer Gordon Willis whose film ethos gave The Godfather its classic, distinctive look that creates its timeless quality.

Coppola and Willis declined to use any modern camera techniques like helicopter zooms, freeze frames, or rapid edits during production, thus the film looks like it could have been lifted from an oil painting or as if it was a tableau painted on a catholic church. The Sicily sequence in particular stands out as an example of this, with the beautiful, barren landscapes resembling a painting more than a film frame. The dark lighting also continues throughout the film as most interior scenes are shot so shadows create a sharp contrast, showing us how the men we are watching exist in the underworld, a separate society governed by tradition, honour, and blood instead of laws, due process, and bureaucracy.

Indeed, it is these conflicting ideas that are central to the entire trilogy’s relationship with America. By 1972 the counterculture had died, and with it an alternative society where love and compassion ruled. The Vietnam War continued to rage as young men offered their lives for what was quickly being described as a meaningless cause. America’s youth had lost its innocence. Coppola’s film represented the America people wanted to believe in. At a time when disillusion and corruption marred politics, and people’s dreams of a new age had been violently crushed, The Godfather offered another form of stylised counterculture to appeal to viewers seeking an updated version of the ever-elusive American dream.

The Father, The Son, and the Family Business

First and foremost, The Godfather is about family. It is the story of a man and his four sons (Sonny, Fredo, Michael, and adopted son Tom Hagen) who worship their father with devotion but also love each other dearly. The dynamic between these five characters in particular is one of the secrets to The Godfather’s continued success all these years later.

However, without the film’s ensemble cast these characters would not be as compelling as time has proven them to be. Marlon Brando’s performance is correctly regarded as one of the greatest ever put to screen. He embodies Don Corleone, nailing the balance between wise elder, doting father, and ruthless yet shrewd mafia Don. His screen presence is simply mesmerising, placing both viewers and the other actors into a trance whenever he speaks.

Al Pacino’s turn as reluctant prince Michael has also rightfully been pinpointed as one of the best of the 20th century but it is James Cann as the hotheaded-heir-apparent Sonny, John Cazale as floundering Fredo, and Robert Duvall as the family’s measured consigliere Tom that bring the film alive. Caan is electrifying and shines during the second act as his energy prevents the pacing from ever getting too pedestrian. Duvall also provides a wonderful contrast to his brothers with his reserved disposition striking a stark alternative to Sonny’s fiery passion.

Finally, John Cazale, who’s talents would later be fully realised in Part II, performs the opening act to one of cinema’s most tragic and heartbreaking characters. As overlooked middle child Fredo, Cazale brings an aura of naivety, innocence, and pity to a character that could have easily been a footnote. It is a great tragedy that Cazale died after only starring in five films (all were nominated for Best Picture) but it is perhaps his performance as Fredo that best epitomises the tragic dichotomy of family in The Godfather.

The Corleones are only successful when the family is in unison but the very nature of family creates conflict. Thus, in the film’s climatic sequence where Michael consolidates his newfound power by ordering his brother-in-law’s death, we see how family can never truly rival the allure of power. Therefore, because Fredo’s greatest sin is idealising his brothers, he exemplifies how The Godfather’s tragedy lies in its deification of family as something sacred because ultimately the immorality of man will always poison blood.

A timeless classic

It is impossible to sufficiently summarise The Godfather in a single article. Fifty years after audiences were first entranced by Nino Rota’s ‘The Godfather Waltz’, Coppola’s magnum opus is still the best film to ever come out of Hollywood.

It is simply unrivalled in its scope and depth, managing to tell a story of Shakespearean proportions with the introspections of a modernist commentary on capitalism and family. Today, The Godfather’s legacy is almost like a classic myth. Its reputation precedes it and no one dares “take sides against the family” but this is all for good reason because, as I hope this article has demonstrated, The Godfather is simply pure cinematic perfection.

Thankfully, the success of The Godfather does not mirror the tragedy of the Corleones. Five decades since it first filled cinemas and swept the awards circuit, it continues to embody everything cinema is, and should always strive to be.