Microtransactions: the scourge of the games industry

By chrisglover

‘Microtransactions’ — you’ll no doubt already be aware of them, even if not by name. The term refers to any small payments of real money for which players receive virtual goods in-game. A staple in free-to-play games — and thus a huge presence in the mobile games industry — the wily business model generates heaps of profit by gnawing at the Achilles’ heel of every gamer: their patience.

To this end, video games driven by microtransactions employ all the psychological manipulation techniques in the book to prise open the wallets of the more suggestible members of their player base, ensuring a sustainable influx of cash long after release. Microtransactions invariably occur via an intermediate currency. Players of Candy Crush Saga, for example, use real money to purchase ‘gold bars’ which can then be used to buy extra lives, moves, or levels.

For developers, the benefits of this devious pay-structure are manifold. Players lose track of real-world value with this unfamiliar currency, obscuring the true extent of their spending, and bulk discounts on in-game currency encourage even higher spending whilst further blurring the real-world value of in-game items.

Craftier still, deliberate disparities between the quantities in which virtual currencies are bought and the cost of items ensure that players often have a small amount of currency left over. Not enough to buy anything with of course, but enough so that they might as well go ahead and buy more currency to bring their wallet up to a usable amount — I mean, it’d be a waste otherwise, right?

So yes, free-to-play developers use deliberately exploitative mechanics to squeeze money out of their players — but why on earth wouldn’t they? Microtransactions in free games simply allow players who enjoy the product to support developers.

Plus, the traditional pay-to-play system of gaming generally doesn’t work with mobile games — data has shown that consumers are reluctant to buy mobile games outright. I, for example, would have turned my nose up at Pokemon Go had it cost £2.99 on the app store, but just a few weeks down the line I was more than happy to fork out £15 for items which gave me a slight edge over my 11-year-old rivals from the local park.

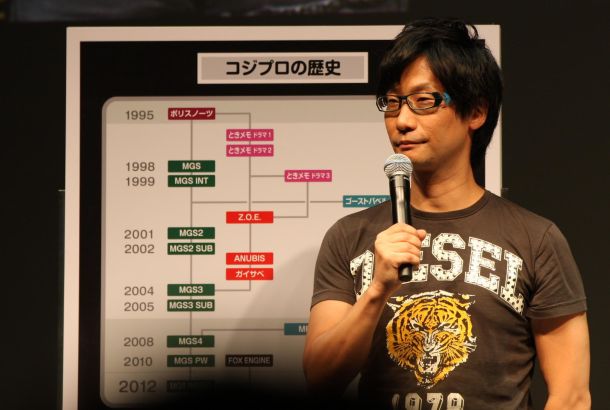

Photo:Stux @pixabayIt didn’t take long before AAA publishers took note of the microtransaction goldmine and had the audacity to start including them in paid titles.

Being pestered again and again to hand over money is acceptable in free-to-play games because it’s the price you pay for enjoying an otherwise free experience. The same pestering in a game you’ve already paid for is, quite frankly, outrageous — though not everyone thinks so. It was reported last year that Rockstar games have made over half a billion dollars — that’s billion, with a ‘b’ — through microtransactions on GTA V’s multiplayer mode.

You wouldn’t buy a house and be expected to pay extra for the “enhanced experience” of having windows. Nor would you pay for a flight, board the plane, and be asked if you’d like “exclusive access” to your designated seat for just a few hundred Jet Tokens. You wouldn’t pay £9,000 a year for a university education, and then be expected to pay to use their printers – just kidding, that last one is completely reasonable.

Now imagine instead of simply buying that plane seat, you were offered a random, mystery box which could contain any one of hundreds of items of plane-related paraphernalia. Upset that you got a soggy ham-and-cheese toastie instead of a seat? That’s okay, just go ahead and roll the dice with another mystery box and maybe then you’ll get the item you wanted.

This exact system — designed to foster gambling tendencies in children and exploit players with addictive personalities — is employed by countless full-priced titles such as Fifa, Overwatch, Destiny 2, and Call of Duty, the developers of which have succeeded in the impressive feat of making ‘microtransactions’ an even dirtier word than it already was.

EA’s in game currency is creatively called ‘FIFA points’ Photo:EASportsWhilst there aren’t enough Gold Bars or Pokécoins in the world to silence my criticism of microtransactions in pay-to-play games, there are many gamers who don’t see them as a problem; who would tell you that my house and plane analogies are unfair and invalid as most microtransaction content is “optional” and “not an essential part of the experience” like windows on a house or seats on a plane.

I will — begrudgingly — admit my analogies err on the side of hyperbole, but consider this: perhaps the true insidiousness of microtransactions in pay-to-play games is that despite how “optional” and “purely cosmetic” their content may be, the game is often still built carefully around this system, affecting even the players who choose not to buy them.

This renders any frustrating aspect of the game as a potentially deliberate inclusion: one of many ploys in a war of attrition designed to make you think spending a few extra quid to improve your experience is the smart thing to do. They’ve sold you a house with windows, yes — but those windows let in just enough of a draught that you pay them for some new ones anyway.

Call of Duty: MWR sells random boxes of cosmetic items. Photo: ActivisionSo what can be done to combat the ever-growing presence of microtransactions in full-priced games?

Regrettably, not a whole lot. The big companies lining their pockets with the system are very good at making people believe microtransactions are just innocuous additions to their games which provide optional extra content. Cynical individuals such as myself can continue to vote with their wallets and not partake in microtransactions, but as long as they continue to generate inordinate amounts of cash, the microtransaction model will continue to spread like the disease it is.

Tommy Palm, the creator of Candy Crush Saga, once said that in the future, every game will be free-to-play and driven by microtransactions. I fear he may only have been wrong about the “free-to-play” part.