The annual Royal Anthropological Institute Film Festival (RAI) was held at the harbour side Watershed in Bristol on the 27-30th March 2019. The festival highlighted some of the best ethnographic documentary films being produced around the world, with six films by University of Manchester graduates screened.

Horror in the Andes

University of Manchester alumni Martha-Cecilia Dietrich opened the second day of the festival with her new feature length documentary Horror in the Andes. The film follows the materialisation of three big time dreamers, Bruce Lee enthusiasts, and determined directors’ passion project, a horror film set in Ayacucho in the Peruvian Andes, which they hope will be just as successful as those produced in “the outside”, AKA Hollywood.

An impressively original documentary subject lends this film to being memorable, sweet, and unique amongst a utilitarian schedule of film-after-film-after-film for the four day event. The relationships between the cast are sincere, their jokes natural, and their passions real. I found myself intrigued by the outcome of the film they were making, genuinely hopeful that it was a success for them.

This is where the documentary left me a bit wanting, however. A particularly wonderful scene finds one of the men showing Martha his Inca statue he bought in Lima. He announces that at the first screening of the film he will get someone to present the statue to him as an award. “Hollywood have the Oscars, we have the Inca!” The brilliance of a scene of a man buying his own award to be presented to him aside, the documentary could have gone further to film this opening night and the presentation of the award. Instead the documentary ends on the three friends editing the film. Perhaps it was a conscious decision to only show the bubble of the film-making experience rather than it be burst with audience reception, but I rooted for these men, and would have enjoyed seeing what became of their horror film.

Certain dips in sound quality during interviews, though frustrating, could be overlooked when the charisma and eccentricity of the film-makers exploded on screen. “People say I am a nutter, but nutters made the world!”

Find out more about the film here.

3.5/5.

Niishii: Night Worlds

UoM Master’s graduate Saranya Nayak created a masterpiece in 22 minutes with her sensorial experience of the town of Dubrajpur in West Bengal, India, at night. Niishii explores the people who inhabit the town after dark. Those selling goods in the night market, secretive husbands hiding from their wives in drinking “dens”, the chitter-chatter of families home to eat, and even the thrills of an amusement park illuminated.

What is excellent about this film is not only the technical triumph of shooting in extremely low light, but also the ability to create a world that seemed so extensive through sound, textures, light, and motion in such a short amount of time. The shot from a swaying ferris wheel, though some what sea-sickening, was a great example of film-making that really evokes a response from the audience (even if that response was vomit).

Nayak uses the space of Dubrajpur’s night world to explore how electricity has effected and changed the place, the people, and the stories told in the town. Those featured in the documentary recall stories of the “light ghost” that used to terrorise the town at night prior to electricity. Men in the drinking den wonder why anyone would want electric lights at all, especially when they are trying to hide from their wives in the first place.

Niishii is an excellent example of a film that completely situates the audience within the world it represents. It’s the last rung on the ladder before virtual reality, and can be seen for free here.

5/5.

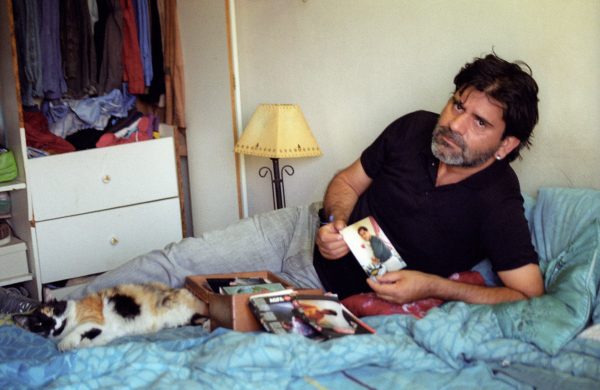

This is My Face

P.h.D scholar Angélica Cabezas Pino is the brains behind this heart-felt observation of men living with HIV in Chile. The documentary follows a number of men diagnosed with the disease in a country that, according to Pino, stigmatises the issue so much that many men live in silence and secrecy surrounding their condition.

For many of these men, the documentary was the first time they were able to publicly express their diagnosis, and as the title suggests, put a face to the disease as an attempt to de-stigmatise HIV in Chile. The trauma these men recall in their accounts on film can only be described as courage many of us will never have to employ.

This film is highly collaborative, and it shows. The men take agency in how they would like to be portrayed. We see them staging their own photo-shoots, telling their own stories their way, snap-shots of what they think the world needs to know about them as men with a HIV diagnosis.

Some scenes are so brutally honest and difficult to watch. One photo-shoot led to Oscar, one of the main men in the film, asking his mother to recreate something she used to do daily: bleaching the entire bathroom after her son had used it, from fears of catching HIV. The confusion and fear around HIV has been prominent in the emotional history of the men, but the message in the film is clear: these men can and do live a normal life, and they want you to know who they are.

4/5.

It Was Tomorrow

Alexandra D’onofrio, UoM P.h.D alumni screened her directorial It Was Tomorrow on three Egyptian men living in Italy who have just been awarded legal residence on the Thursday of the RAI festival. After living in Italy for ten years undocumented, being granted legal residence means security and belonging that the men have been desperate for for a decade.

The film began strong, with beautiful use of line animation to illustrate what it’s like to be trapped, refused access and objectified in the immigration process. The film focused on memory and place in the interviews and shots. However, the powerful message the animation portrayed began to feel slightly lost on a road of different kinds of artistry and drawings to animate the mens memories, which felt at times confusing, and occasionally unnecessary.

Memory is a difficult topic to visually represent in documentary film, and It Was Tomorrow didn’t quite make these memories condensed enough to stay engaged for a 52 minute run. However, the film-maker tackles an extremely politically charged and important issue with incredible access to very personal stories told by these men and should be congratulated on her exploration of immigration, access and longing for home. As a PhD project it was inspiring to watch, especially as many of the other films had a far bigger crew and far more funding behind them.

2.5/5.

Amazonimations

Unsatisfyingly short, simply because it was so enjoyable, Amazonimations is the collaborative project between P.h.D scholar Camilla Morelli, animator Sophie Marsh and the indigenous Matses people of the Amazon rainforest. The film covered multiple stories that the Matses people wished to tell such as their use of poisonous frog’s blood, the children’s tales of the animals that roam the rainforest (and which ones are the tastiest), as well as what happens to those that move away to cities.

Powerfully, the latter reminds the audience that just because Matses are indigenous does not mean that they cannot wear trousers and trainers. Holding a job as a cleaner in a city does not make them any less indigenous. The city Matses hold signs that say: “We have the right to change”.

The animations themselves are well illustrated with colour and sounds of the rainforest. The children’s stories use drawings made by the Matses children themselves, much like something you would see tacked to a fridge door by a proud mother in Chorlton.

Amazonimations manages to touch upon the unknown and the familiar in what feels like a playfully animated storybook, all within an impressive seven minute running time.

You can find out more about Amazonimations here.

4.5/5.