Based on George Bernard Shaw’s 1913 stage play Pygmalian, My Fair Lady premiered on Broadway in 1956 and transferred to the West End two years later. Both versions starred Dame Julie Andrews DBE and Sir Rex Harrison. The film adaptation (1964) controversially replaced Andrews with the then-better-known Audrey Hepburn. The musical has had quite the journey, and it’s now back on the West End for the first time in two decades!

The current West End version is a transfer of the 2018 Broadway revival (produced by Lincoln Center Theater and Nederlander Presentations, Inc.) – presented by the English National Opera at the London Coliseum.

The London Coliseum is the largest theatre in the West End and second largest in London (if we include the Hammersmith/Eventim Apollo as a theatre and not as a music venue, that is). The theatre is perhaps the most beautiful I’ve ever seen – there are even sculptures of chariots at the top of the walls at either side of the stage! It’s not just beautifully designed but practically, too – the stalls’ raking is some of the best I’ve ever seen in a theatre. Like the Barbican Theatre, each row is on a step, so no matter where you’re sat, you’re a step above the row in front of you (like the circle and grand circle).

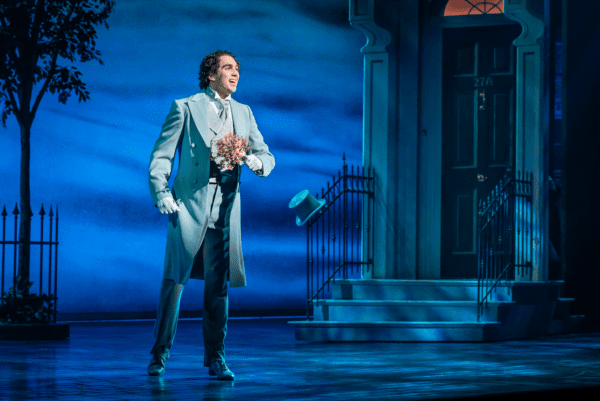

The West End production stars Harry Hadden-Patton (who was nominated for a Tony for the role on Broadway) as Professor Henry Higgins, Amara Okereke as Eliza Doolittle (the first Black actress to take on the role), Stephen K. Amos as Alfred P. Doolittle, Dame Vanessa Redgrave DBE as Mrs. Higgins, Malcolm Sinclair as Colonel Pickering, Maureen Beattie OBE as Mrs Pearce, and Sharif Afifi as Freddy Eynsford-Hill. Sadly, Redgrave was off when we went to see the show, but I did catch her Q&A a the premiere of Mrs Lowry & Son a few years back.

The Cast

Tony and 2 x Screen Actors Guild nominee Harry Hadden-Patton is best-known for La Vie en Rose, Posh (original cast), About Time, Downton Abbey, The Crown, Versailles, and Flying Over Sunset (original Broadway cast). He was every bit as excellent as one would expect from such an acclaimed actor – and one who received a Tony nomination for playing the role on Broadway. He showed a slightly softer side to the arrogant and insufferable Professor. He was surprisingly likeable – if only by virtue of being hilariously hideous!

Olivier nominee Malcolm Sinclair has played the role of the Colonel on the West End previously – and he’s still got it! Sinclair is very well-known onstage and starred in the West End revival of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Jeeves – a very different production, renamed By Jeeves. He was nominated for an Olivier for starring in Privates in Parade. Onscreen, he is known for Pie in the Sky, V for Vendetta, and Casino Royale. Whilst Colonel is your quintessential, loveable old man, Sinclair set himself apart from what is sort-of a stock character in theatre. There was a delightful delicacy to his performance.

RTS winner and BAFTA nominee Stephen K. Amos was LOL-funny – living up to his reputation as a comedy legend. Whilst the musical was long and could feel a little heavy at times, Amos consistently brought comedic relief. In particular, his transformation in Act 2 was hysterical. Amos’ hard-hitting documentary Batty Man was nominated for a BAFTA, and now he’s doing musical theatre – is there anything this man can’t do?

Maureen Beattie OBE is an acting icon, known for Casualty, The Chief, All Night Long, Bramwell, Wing and a Prayer, The Bill, and Dreadwater Fell. She was thoroughly likeable as the proper Mrs Pearce.

Sharif Afifi was excellent as the excitable Freddie – a brilliant representation of young people being more open to difference and change.

Whilst Redgrave – one of the most-awarded actors of all time and one of the few performers to have achieved the Triple Crown of Acting – was sadly off, her understudy, Heather Jackson, was very well cast as Mrs Higgins. At first intimidating, later welcoming, but always elegant – Jackson embodied her perfectly.

Then there’s the little-known leading lady, Amara Okereke. Little-known, you say? Not for long! Okereke is surely going places. As Doolittle, she is instantly captivating and commands your attention for the whole three hours that the musical runs.

The Attention to Detail

Whilst the script is problematic, one can appreciate it as a product of its time – and I cannot deny the magical feeling one gets when watching an iconic, old musical brought to life. You get a nostalgia for a time you never knew – a time you should never want to know, for it was pretty awful, but still, the feeling is one of warmth, yearning and appreciation. There’s nothing quite like it.

The script has many flaws, but one cannot find a single fault with the musical’s production value. There were no expenses spared.

Funnily enough, it did not seem that way at first. Before we were introduced to high society, we were on the poor streets of London – which were created using 2D models that looked like cardboard cutouts – well-done, yes, but still, cardboard cutouts!

Then, we were transported to Higgins’ residence. At first, we were in his library – which looked just like the inside of a personal library, complete with a winding staircase and a first floor. This piece of set span around: the other side was a living room, and there were two small rooms at the sides: one was more dynamic and was first used as a bathroom, whilst the other appeared to be a garden terrace, complete with a tree – though we never saw this head-on; we just saw it through the windows (yes, there were even windows).

Higgins’ home was miles away from the surprising simplicity of the previous set. Granted, the scenes in the poor part of town just take place on the streets, so it’s understandable why 2D sets were chosen – but this was contrasted with the scenes that took place on the street outside Higgin’s residency, which used elaborate set just to create a door! Rather than being about saving cost, it was quite clear that the creatives were attempting to create a contrast between the rich, sumptuous, 3-dimensional world of the aristocracy and the dull, thoughtless, flat (literally) world of the working-class.

The costumes are some of the best I’ve ever seen onstage. In particular, the colourful gowns seen in the first scene of the second act, and the ivory gowns seen in the racecourse scene in the first act.

Whilst I’ve never seen the stage musical before, nor the film, I’m a huge Audrey Hepburn fan, and I recognised a few of the musical’s costumes as ones that Hepburn wore. Most noticeably, Doolittle’s black and white racecourse dress. Whilst the film version sees the entire ensemble wear black and white, this production saw Doolittle become a “black sheep” surrounded by a sea of whites (quite literally, racially). It was just another example of the production’s clever creativity and awe-inspiring attention to detail.

The “New” Eliza

Okereke’s casting follows a trend of (finally) casting Black actresses in lead roles in musicals (e.g. Christine Daaé in The Phantom of the Opera, Belle in Beauty and the Beast and the understudies for Elsa in Frozen and the title character in the recently-closed Cinderella).

But there’s something interesting about casting a Black actress as the titular My Fair Lady. It adds another layer – the story becomes not just one of class, but also race. The pompous White man is now attempting to change not just a poor woman but a poor, Black woman – forcing her to “fit in” with his kind.

However, upon watching the production, it became clear that race was not a thing – the casting was colourblind, with all races playing members of both classes, and race never even being alluded to. It was pleasantly post-racial, as theatre should be (except where race is important). Sure, race was never a thing in this musical, but casting a Black woman as Doolittle and then never acknowledging race (not even subliminally) is something of a missed opportunity.

That said, I can still appreciate that casting a Black woman as Doolittle seems to be sending a certain message – especially with the changed ending (first seen in the 2018 Broadway revival), in which Doolittle leaves Higgins (with a smile upon her face).

Indeed, the ending was wonderfully done, with Okereke walking off-stage and into the audience. She doesn’t just leave Higgins; she leaves the theatre – for that is what her life has become: theatre, e.g. Higgins forcing her to be somebody she was not, keeping up appearances, etc. Doolittle exits the story Higgins crafted for her, but not before getting the last laugh (or, rather, smile) – the “duff duff” moment of the musical. She sets off to live her own life and tell her own story. She is no longer his fair lady.

For those who don’t know, the original musical ends with implied coupled contentment for Higgins and Doolittle – after he transforms her into a proto-Stepford Wife. Surprisingly, Pygmalion actually ends with Doolittle leaving Higgins. The creators of the musical did their own “my fair lady” to the story – ridding it of its feminism. This reminds me of Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, which ends with Nora leaving her husband – but the stage adaptation saw her choose to stay and, worse, be tucked in by her husband/owner.

My Fair Lady’s new ending, then, is not so new, but, rather, a reclamation of the original ending that was discarded in order to further oppress and marginalise Doolittle.

Now, the reclaimed ending, nor all the Suffragettes in the world (that Suffragette scene was brief but beautiful), is not enough to make up for the musical’s undeniable classism – made worse by the fact the crowd is quite possibly the (first-)classiest theatre crowd you ever did see! But, in the end, the poor, Black woman wins.

Isn’t that just… loverly?

My Fair Lady plays at the London Coliseum until 27th August, before beginning its UK tour a month later, at The Alhambra Theatre, Bradford, from 22nd September until 2nd October. The final date, so far, is Birmingham Hippodrome, from 8th until 26th March. More dates are expected to be added to what is currently only a 6-city tour – one hopes we get it in Manchester!